Even though this might be your initial thought, a plant patent is not a right-giving exclusive protection for an industrial manufacturing building, nor is it about protection for a secret, undercover informant.

It is actually a form of legal protection for rock n’ roll-related inventions and the name is a tribute to legendary lead singer Robert Plant from the band Led Zeppelin.

Okay, okay, I’m kidding (not about the legendary part though — they do rock).

Plant patents are, as you probably guessed by now, about plants — as in, those living, growing, and (often) beautiful organisms that cover this green Earth.

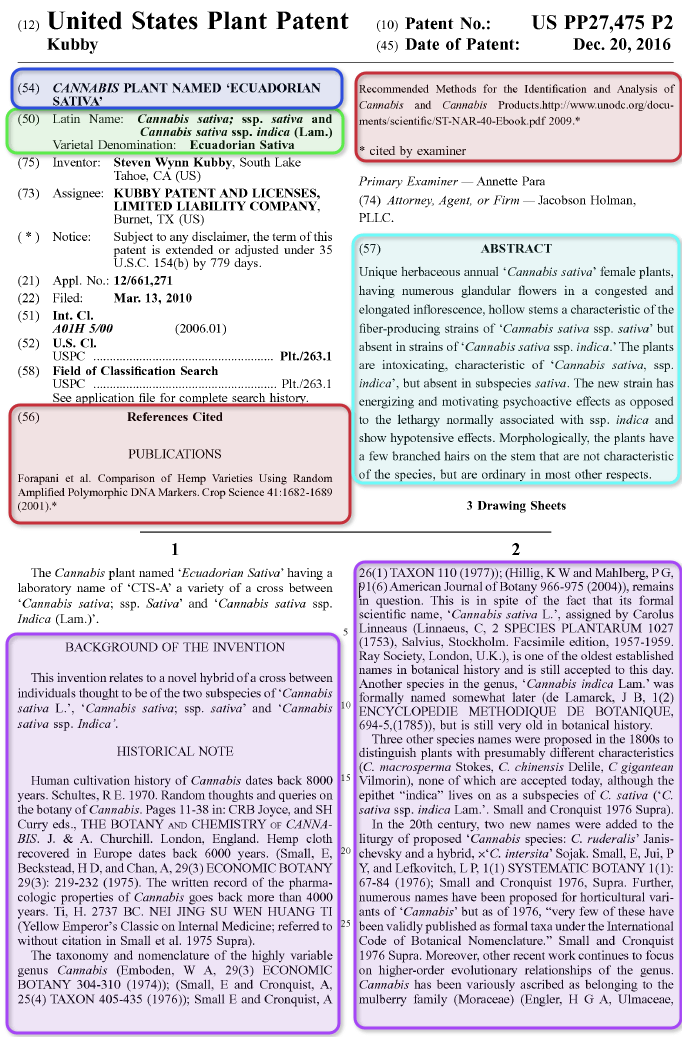

And yes: that, above, is the cannabis plant — a huge topic and rapidly growing industry, and a great example to use when discussing plant patents.

There are some major issues surrounding cannabis and patents though, and a very well-written article I found on the subject can be found here. You can read another article focused on cannabis patents specifically here.

Lastly, check out this fun video I put together which explains how this federally-controlled substance that many states have legalized is still on some shaky patent waters:

In this article below, I’m going to discuss the steps that you should take in order to file a plant patent in the United States, and what every inventor, botanist, or herbalist should know along the way.

Before we begin…

KEY REFERENCE: Here are some great references to check out to find this information: on the USPTO website here, and also in the law itself (for those overachievers) here (35 USC 161).

BIG TIP: One of the best tips from the USPTO.gov website is that if you’re drafting your first plant patent application, you should model the application after one that has already been granted. Use the same or similar format!

Interesting in learning How to Patent an Idea? Check out my in-depth 13-step article by clicking here!

Step 1: Determine Inventorship (Ownership)

Before going any further down this process, it is critical to identify who actually invented the new plant.

By definition: an inventor is an “individual(s) who invented or discovered the subject matter of the invention.”

In this definition, there’s actually a lot packed in there — notice the “(s)” by individuals. This means that there can be more than one inventor, just like utility and design patents.

Also notice the fact that it’s not necessarily the person that brought about the invention (in physical form) — it’s actually the person(s) that brought about the “subject matter”. This is huge.

There may be a lot of steps needed in order to develop a plant invention, as it’s very possible that there are one or more co-inventors. However, just by virtue of reproducing the plant and getting it to propagate, does not make them a co-inventor. To become a co-inventor, you’ve got to contribute to the creation or discovery process.

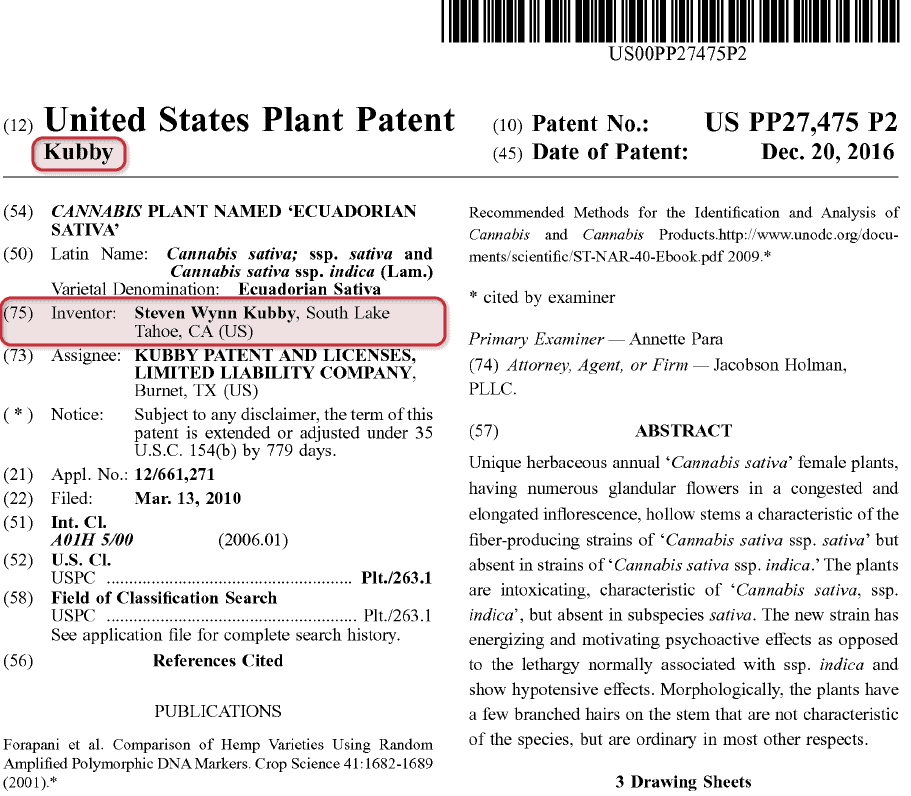

Here is where the inventors are listed on the cover of an sample plant patent called “Cannabis Plant Named ‘Ecuadorian Sativa’: PP27,475.”

As shown above, you can see who the inventor is on a plant patent (highlighted in red rectangles). The last name is identified in the header (“Kubby”) and full details below (“Steven Wynn Kubby”) and also identified the city where the inventor resides.

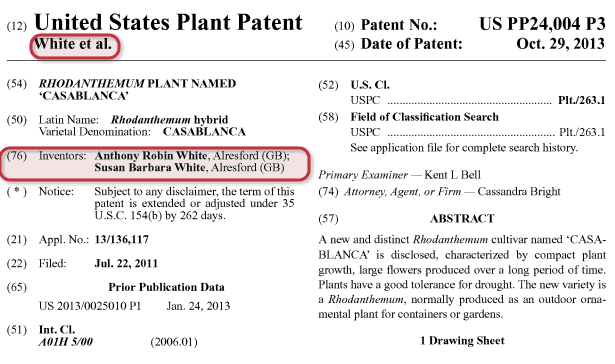

If there are multiple inventors, the patent office will simply publish them in the order they were identified on the application data sheet for the filing document when the application was submitted. On the top, it will show the last name of the first inventor and simply state “et al,” which is latin for “and others”.

You can also see below that the inventors are from Great Britain (hence the “GB”) not the United States (US) as in the example above. Here is an example of how it shows up on PP24,004:

Whew! We’ve covered a lot and that’s just step 1. Once inventorship is sorted out, you will need to make sure that your plant even qualifies for patent protection!

Step 2: Determine Plant Patent Eligibility

To be able to get a plant patent, it has to fit in the legal definition of what is protectable under 35 USC 161.

Check out this video for a great primer on plant patent eligibility:

Here is the verbatim definition for what qualifies as an eligible plant patent:

“Whoever invents or discovers and asexually reproduces any distinct and new variety of plant, including cultivated sports, mutants, hybrids, and newly found seedlings, other than a tuber propagated plant or a plant found in an uncultivated state, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title. (35 USC 161).”

“A plant patent is granted by the United States government to an inventor (or the inventor’s heirs or assigns) who has invented or discovered and asexually reproduced a distinct and new variety of plant, other than a tuber propagated plant or a plant found in an uncultivated state.” (uspto.gov)

Let’s unpack this a bit. There likely are some terms here that you may not fully understand or appreciate. Let’s make sure we’re clear on them:

“Asexually reproduced” simply means that the plant grows without fertilized seeds. It is instead able to be reproduced without synthetic means.

Surprisingly, there are a large number of ways in which plants may be asexually reproduced, comprising of: rooting cuttings, grafting and budding, apomictic seeds, bulbs, division, slips, layering, rhizomes, runners, corms, tissue culture, and nucellar embryos. (Definition and further explanation of these types of methods is beyond the scope of this article!)

“Other than tuber propagated plant”: A tuber plant is one in which the part that can be eaten is actually part of the stem or the root of the actual plant or flower — as in the potato, or onion, the part of the plant being discussed is underground. This is ineligible for patenting.

Many types of plants require fertilization in order to be reproduced — in fact, most plants in nature require pollination to propagate.

For those seed-based or tuber plants, while there US Patent protection is not possible, there is another great area of intellectual property protection (called “certificates”) that is offered through an office of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) called the Plant Variety Protection Office (PVPO).

Here’s a quick video I put together explaining the PVPA in more detail:

The PVPO will issue certificates which function just like patent rights to exclude others use of them. 100-200 certificates are issued each year — here is the most recent report from November 2018.

In addition to the PVPO, there is yet another avenue of protection is possible for many inventors that are innovating in the plant industry. If a new and non-obvious method of cultivation has been created, a new plant gene (GMO seed) is chemically formulated, or apparatus or device used for the processing, cultivation, lighting, etc. is designed, it is very likely that Utility Patent protection is available.

For much more information about this, please explore our blog post about Utility Patent Eligibility.

Examples will help break this down and make it more understandable. I will use this below example of the first known patent for cannabis that I have found. This will help me lead into a brief discussion about cannabis in later steps.

The plant patent number is PP27,475 (you can see the patent number and title in green rectangles below) and you can see the entire patent document by following that link.

Here’s a short video I did explaining cannabis and plant patents:

Just like utility patents, plant patent inventors get to enjoy 20 years of exclusivity (from the date of filing) to prevent others making, using, selling, or importing the plant into the country.

At this point, hopefully, your plant variety is protectable under US plant patent law. If so… let’s keep moving on.

Step 3: Determine Patentability

Just like utility and design patent applications, in order for an examiner to allow the patent to issue (and rights to vest in the inventors), they have to show that they are one of a kind (among other things).

For a comprehensive discussion on how to perform patentability searches, check out my article How to Perform a Patent Search in 6 Steps.

A novelty and nonobviousness search for utility or design patents would be conducted in a nearly identical way.

In order to be patentable, the following must be true about your plant:

- Eligible: It must have been invented or discovered in a cultivated state and asexually reproduced (See step 2 above).

- No prior public use or sale: That means that the plant has not been patented, in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public prior to the effective filing date of the patent application with certain exceptions.

- Novel: That means that the plant must be shown to differ from known, related plants by at least one distinguishing characteristic, which is more than a difference caused by growing conditions or fertility levels, for example.

- Non-obvious: That means the invention would not have been obvious to one having ordinary skill in the art as of the effective filing date of the claimed plant invention.

Step 4: Draft the Plant Patent Application

Hey! Attention! As a little disclaimer, I want to make sure that if you’re reading this blog, you are made aware that it is accurate to the best of my ability. However, it is accurate only as of the time it is published.

I just want you to know that uspto.gov is going to maintain all requirements for application submittal and should be the main source you use if you’re going to proceed with filing on your own, or to get the latest.

This article will still (hopefully) prove to be worthwhile for years down the road as a general guide.

(I usually let this go without saying… but I’m just saying.)

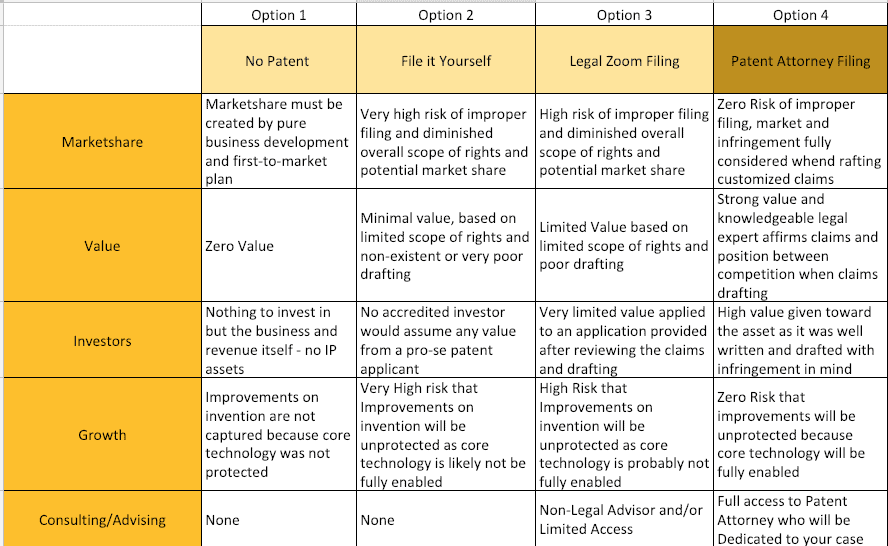

You really shouldn’t file a plant (or any) patent application on your own — don’t do it! I’m a little biased, I understand. But, I’ve drawn up this chart (below) for your consideration: some reasons why you should chose to hire a professional patent attorney to file your patent application. Check it out:

For the best results, be sure to hire a patent attorney. Make sure to confirm that they are actual patent attorneys. It sounds silly, but you’ve got to do your homework. You can look them up to confirm here.

I also wrote this handy article called “Top 10 tips when meeting with a patent attorney.”

(Okay. Let’s get back to the good stuff.)

There are two prerequisites that must be completed before filing a plant application:

- Discovery step: Must discover or identify a novel plant that was found in any of the following ways:

- Grown in any cultivated area

- In a monoculture or known variety

- Desirable mutant which was either spontaneous or induced

- Recognized as an outstanding single outlier within a progeny as part of a planned breeding program

- Asexual reproduction: Must asexually reproduce the plant by:

- Testing the stability by propagating clones of the same genotype

- Analyzing each close to confirm the one or more unique characteristics are present in order to confirm that the unique characteristics were not caused by some disease, infection, or some other transitory change.

Once the two steps are complete, you are ready to submit your plant patent application. But what should be written in the “specification” (the written description) of a plant patent application?

Title 37 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Section 1.163(a), requires that “the specification [of a plant patent application] must contain as full and complete a botanical description as reasonably possible of the plant and the characteristics which distinguish that plant over known, related plants.”

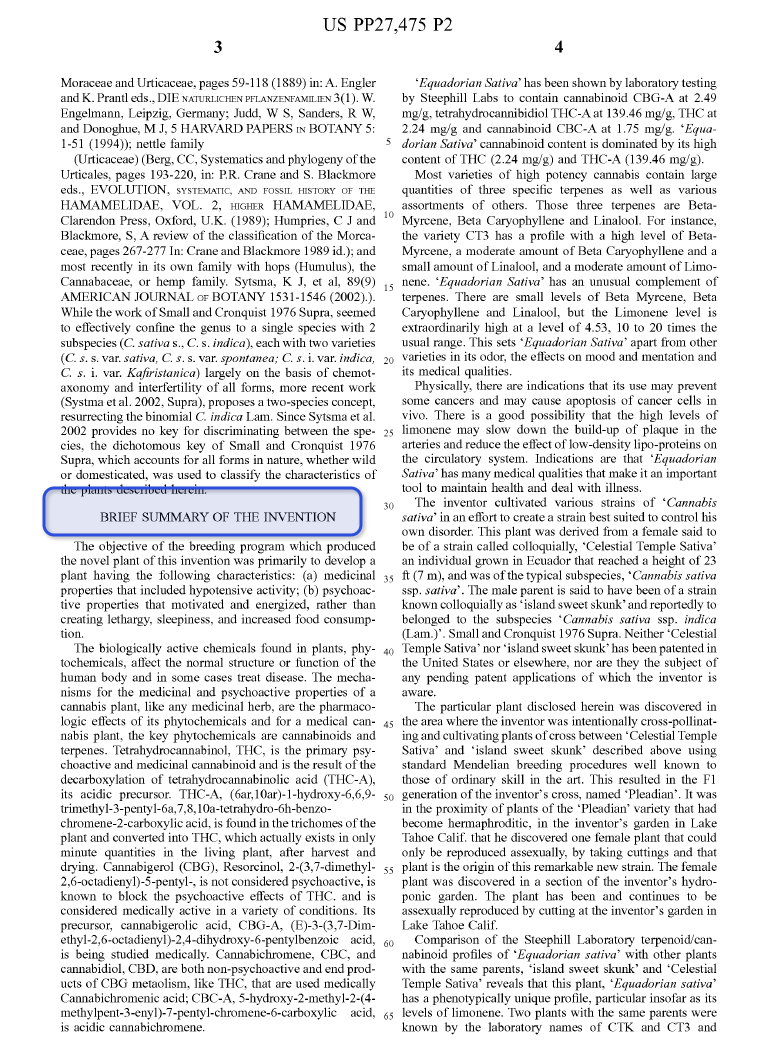

Let’s break it down into the various sections, and I’ll use color to guide you!

Title: The title of the invention may include an introductory portion stating the name, citizenship, and residence of the inventor(s).

Make sure that the name of the plant you are seeking protection for has not already been taken by any other named plant species. A great place to search to make sure the plant name is not already taken can be found at the site called Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV).

Related Applications: Related applications may include:

- A utility application from which the claimed plant is the subject of a divisional application.

- A continuation (co-pending, newly filed application) to the same plant filed when a parent application has not been allowed to a sibling cultivar.

- An application not co-pending with an original application which was not allowed.

- Copending applications to siblings or similar plants developed by the same breeding program, etc.

Latin Name and Varietal Denomination: The Latin name of the genus and species of the plant claimed as well as the Varietal

Abstract: The abstract is a short description that can be understood by a lay person (someone not a botanist/plant specialist). It will describe the plant generally and include the most notable or novel and important functionality or characteristics.

Background: Includes the Field of Invention and a description of the relevant prior art.

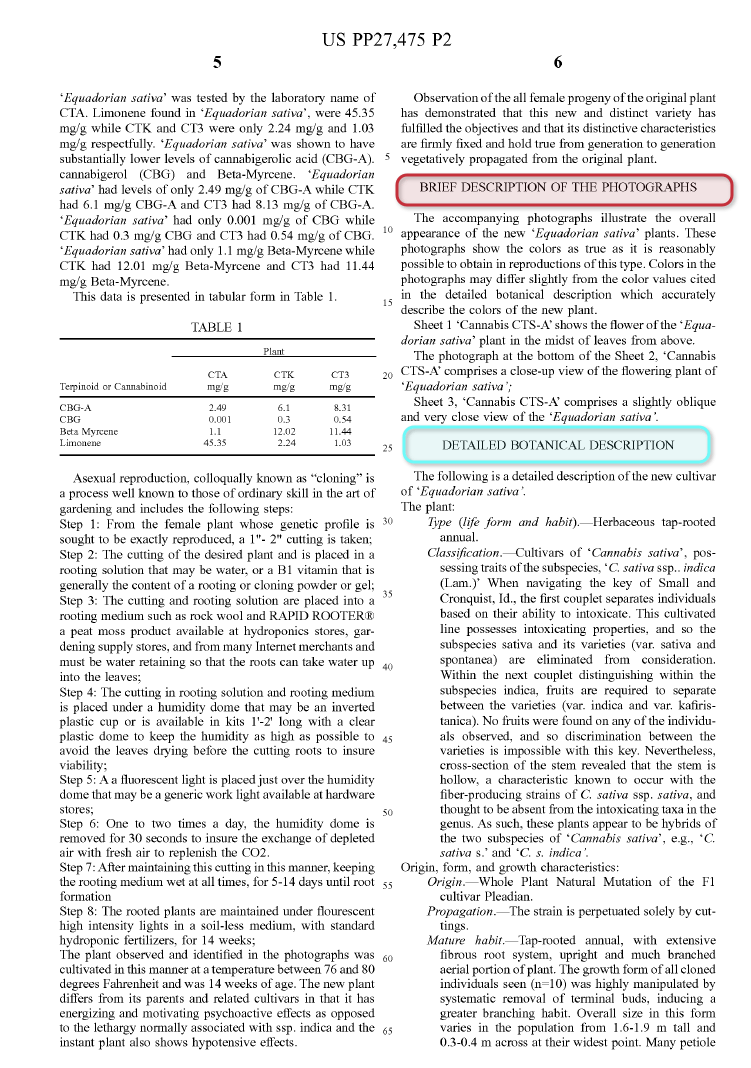

You can check out the image below, our example Plant Patent PP27,475, which will have each of the above sections highlighted in the respective colors:

Summary: In the summary section (on page 2 of the example, below), the key functionalities and characteristics of the plant are described. The narrative or a list should spell out how this plant differentiates itself from others in the same species and class and what the consumer benefit will be.

Brief Description of the Drawing (or Photograph): This is self-explanatory and is truly a natural language explanation of what is shown in the drawings or the photo. It can include perspective, angle, and whether its a partial or complete view.

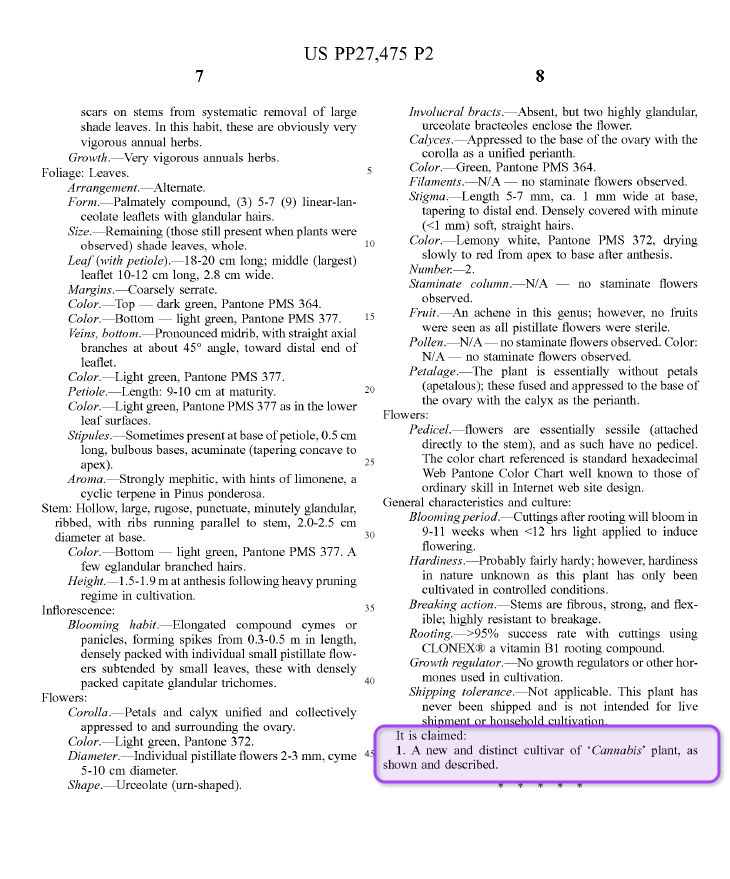

Detailed Botanical Description: This section must be a complete botanical description of the claimed plant.

Without going into too much detail, the following are parts of the plant that must be fully described for the USPTO to consider the detailed botanical description to be complete:

- Genus and species

- Habit of growth

- Cultivar name

- Precocity

- Botanical characteristics of plant structures (i.e. buds, bark, foliage, flowers, fruit, etc.)

- Fertility (Fecundity)

- Other characteristics which distinguish the plant such as resistance(s) to disease, drought, cold, dampness, etc.; fragrance, coloration, regularity and time of bearing, quantity or quality of extracts, rooting ability, timing or duration of flowering season, etc.

The USPTO site gives a very good explanation of what should be in the plant spec:

“Specification of the genus, species and market class may begin this section, and the parents of the claimed plant may be specified in the initial part of this section. The growth habit of the plant should be described as to the shape of the plant at maturity, and branching habit.

“The characteristics of the plant in winter dormancy should be completely described, if appropriate. A complete botanical description of bark, buds, blossoms, leaves, and fruit should be a part of the disclosure. Plant characteristics which are not capable of definitive written description or which cannot be clearly shown must be given substantive attention in this portion of the application.

“These would include, but not limited to, fragrance, taste, disease resistance, productivity, precocity, and vigor. Even if the characteristics are well depicted, the botanical characteristics must be substantively described. The descriptions in this section should be botanical in nature and should be in terms of the art of the plant.

“The detail of this section should be sufficient to prevent others from attempting to patent the same plant at a later date by simply describing the plant in more detail and with the allegation that the original patent did not state the characteristics being further described.”

Claim: You only get ONE claim! Claim drafting is truly an art, and should be left to the trained professional — a patent attorney. Nonetheless, the claim for a plant patent should be constructed with the following in mind:

- Written as a single sentence

- Must be in formal language covering the plant as shown and described

- The language should be drawn to the plant as a whole.

- The clauses should point out and distinctly claim the unusual characteristics of the plant.

- The claim set should not claim parts or products of the plant.

The Drawing(s) or Photograph(s): The key for the drawings is that they must showcase the most distinctive and novel features. Basically, whatever is stated in the claim language from above needs to be shown in the drawings or photographs.

It is also a requirement that the photo or drawing be no smaller than 50% to scale of the actual plant. There is a requirement that the drawings be photographs and that they be in color if one of the features that is being claimed deals with color.

Step 5: Filing of Plant Patent Application

Filing a plant patent application very much follows the same procedures as a utility patent application and the USPTO incentivizes inventors to use the electronic filing method by charging a lower fee for such filings.

Note that before a plant patent application can be submitted, all parts of the plant should be thoroughly observed for at least one growth cycle and any observations or findings should be recorded in detail and submitted along with the application.

Details on how to go about filing a patent application can be found in our other blog on how to file a provisional patent application.

In Conclusion

That is all of the information that you might need to start exploring the world of plant patents. And remember, if this is a route you are considering taking, we highly recommend connecting with a patent attorney!

They’ll be able to assist you with every step of the plant patent process and make sure you don’t miss a thing.

To recap, when filing a plant patent application make sure to follow these 5 steps:

- Determine Inventorship (Ownership)

- Determine Plant Patent Eligibility

- Determine Patentability

- Draft the Plant Patent Application

- Filing of Plant Patent Application

If you would like more information as to how to communicate with your patent attorney about patents, then check out our article, 10 Tips for Inventors: Meeting With A Patent Attorney.

If you are ready to Go Big and Go Bold℠ ! Click here to book a free consultation!

Let us know: what did you find most helpful about this article? What else were you wanting to know about plant patents? What other patent information do you wish you knew?

—

Legal Note: This blog article does not constitute as legal advice. Although the article was written by a licensed USPTO patent attorney there are many factors and complexities that come into patenting an idea. We recommend you consult a lawyer if you want legal advice for your particular situation. No attorney-client or confidential relationship exists by simply reading and applying the steps stated in this blog article.