“How Do I Patent an Idea?”

The real answer to this question is: you can’t.

That’s right, you can’t get a patent for an “idea” alone, not even the best idea in the world.

My name is J.D. Houvener, a patent attorney at Bold Patents Law Firm. My goal for this article is to give you everything you need to know on how to patent an invention.

Since this article covers a lot of important information, I included a table of contents/navigation menu for your convenience. Feel free to skip ahead to any section that interests you.

(For your visual learners, here is a video I created to help you understand the basics of getting a patent for an idea.)

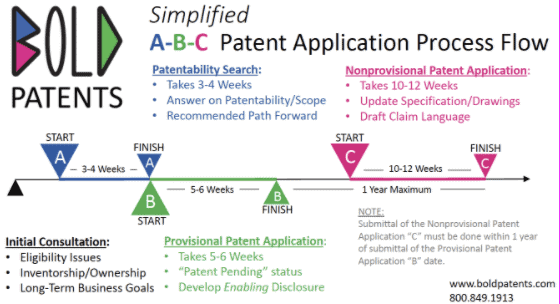

In addition, here is a simplified patent application process flow chart showing the 4 major steps to patenting your idea.

They are even color-coded throughout this article to help you understand what part of the process you are at.

- Prep Work – Small tasks we recommend you complete before you start the patent process.

- Patent Search – Searching the database of existing patents. Ensuring the marketability of your invention.

- Filing Your Patent – Decided on the best course of action. Design, Utility, Plant, Continual, International, etc.

- Post Filing – Responding to office actions, appeals, creating profiles, etc.

I must take a minute and feature our “Patent Chart”, which is the single most important chart showing the 3 major steps (I call it the “A-B-C Patent Flowchart” as well). It showcases the Patent Search, the Provisional, and the Nonprovisional Patent Application, the key timing considerations and major deliverables:

Chapter 1: Prep Work

Before you even think about hiring a patent attorney or attempt to do the patent filing process on your own (not recommended) there are some important questions you need to be able to answer.

If you have already done these, feel free to skip to Chapter 2 where you will learn about how to perform a patent search & ensure the marketability of your patent.

Step 1: Do You Have an Idea or Invention?

(CH1 – Prep Work)

When I give legal advice to first-time clients, it always hurts to tell them, “ideas are a dime-a-dozen.”

Here is a list of reasons why they need to hear it:

- Most inventors (not all) this will fire them up and motivate them to want to strive to work hard to get their invention to a stage of “invention”

- Clients will gain an appreciation for the diligence and hard work it takes to fully conceive of an eligible invention that has practical application* [See new blog on Patent Subject Matter Eligibility]

- It helps to give pause to quick flashes of genius and innovation to think about whether the idea has enough merit in the market to warrant further investigation

Inventors that have done their homework respond by giving me the following:

- Drawings or examples of how their invention would work or could work

- Tell me about how feasible it would be to build a prototype

- Describe the materials they would need to gather

- The order they would need to assemble the device

- What component systems would be required for the idea to work

Once you have an idea that can be described in such detail so that someone could build it just by reading the description and viewing the drawing – then you have identified an invention.

When having the discussion please enter it with an open mind. Many times I speak with clients and try to give them helpful advice but they are stuck in their ways making assumptions with regard to the surrounding technology. Take the critique, it might end up saving you thousands of dollars and headaches down the road.

Helpful links:

- Blog Article: How to Invent Something in 10 Steps

- Blog Article: Confidentiality Agreements: What Are They? When Do You Need Them?

- Blog Article: 10 Tips for Inventors: Meeting with a Patent Attorney

- Great Video describing the ABC Patent Flowchart

- Another reason I love to point out how ideas are “dime-a-dozen” is to point out how courageous the client is being by acting. We encourage our inventors to Go Big Go Bold℠ !

(CH1 – Prep Work)

The patent statute, 35 USC 101 tells us that any:

“new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof is eligible for patent protection.”

While that list of what is eligible seems quite broad (and it is), there are some things that clearly fall outside of that definition and have been solid agreement from courts over the years.

Get an Eligibility Opinion

You need to seek an Eligibility Opinion from a licensed and registered USPTO Patent Attorney, who understands the recent case law and can help you decide whether to go down the patent route or find another.

Your attorney will probably not tell you in black-and-white terms:

“…You should seek a patent on this,” or “you shouldn’t seek a patent on this.”

Instead, you will receive a careful opinion that covers different aspects of your invention and places weight on certain characteristics to give you a level of risk to proceed.

With so much changing in the courts, and with the USPTO examiners, there is no way to be 100% certain about anything, so the opinion will just give opinions on risk and it will be up to you whether you proceed.

TAKE BOLD ACTION NOW: Are you ready to book a consult now? Get on our calendar today!

Helpful Links:

- Blog Article: Is My Idea Patentable? (The #1 Question to Ask…)

- Blog Article: Is My Invention Eligible for Patenting? 3 Simple Steps

- Blog Article: Business Method Patent

- Blog Article: Cannabis & Patents: What’s Coming Next?

- Blog Article: Can You Patent an App? 7 Steps to Patent an App!

Step 3: Determine Who the Inventors Are and Who Will Own it

(CH1 – Prep Work)

After you talk with a Patent Attorney, and signs point to eligibility, you are on your way to getting a patent for your idea!

There are TWO big questions to address right up front so that they don’t trip you up down the road.

Inventorship & Ownership.

1. Inventorship – Who is the Inventor?

“Who invented this? Were there any third parties, contractors, developers, employees involved in the conception of the invention?”

These questions will become very important as the inventor prepares to provide a required oath disclosing all known inventors, under 37 CFR 1.66.

A question that comes up a lot is about individuals or entities that helped to create a prototype or developers that made a software type application.

The simple answer is that these people are likely NOT the real inventors.

Whether through admission, knowledge or through discovery via the inventorship inquiry above, it is critical to identify all co-inventors prior to filing a patent application.

“All co-inventors must be named on patent applications by law.”

Co-inventors, get equal rights as any of the inventors to have exclusivity to the ENTIRE invention to prevent any (non-inventor) in the applicable jurisdiction from making, using, selling or importing the invention.

That also means that no co-inventor can prohibit another co-inventor from exercising their rights to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing the invention. These rules are true so long as the inventor has not assigned their invention to another individual or entity (see patent assignments).

If you’ve co-developed or think you are unsure about who the inventors are in your project follow the steps below or click here to book a free consultation to get help.

Not sure who the inventors are? Take these steps:

- Decide on the scope of the invention (see invention disclosure above)

- Document date(s) of conception for the invention above

- Make a list of all parties that were involved in the invention

- Who in that list merely helped to develop/prototype/manufacture the invention? NOTE: These are NOT co-inventors

- Who in that list contributed to the functional aspects of the invention? NOTE: These are co-inventors of any utility patent applications

- Who in that list contributed to the design aspects of the invention? NOTE: These are co-inventors of any design patent applications

How to make the invention disclosure process easier for your Patent Attorney:

- Prepare sketches, drawings, or photos showing how your invention looks (and could look) with attention to hard to see details with inside/cut/angled views

- Write down instructions on how you would build your invention (physical or digital)

- Think outside the box in terms of materials, methods, applications, and industries that could benefit from the utility or design of your invention

- Simplify, Simplify, Simplify: Distill your invention in a format that is as simple as possible – what is the core innovation?

Six Steps to Determine Inventorship

- Decide on the scope of the invention (see invention disclosure above)

- Document date(s) of conception for the invention above

- Make a list of all parties that were involved in the invention

- Who in that list merely helped to develop/prototype/manufacture the invention?

- NOTE: These are NOT co-inventors

- Who in that list contributed to the functional aspects of the invention?

- NOTE: These are co-inventors of any utility patent applications

- Who in that list contributed to the design aspects of the invention?

- NOTE: These are co-inventors of any design patent applications

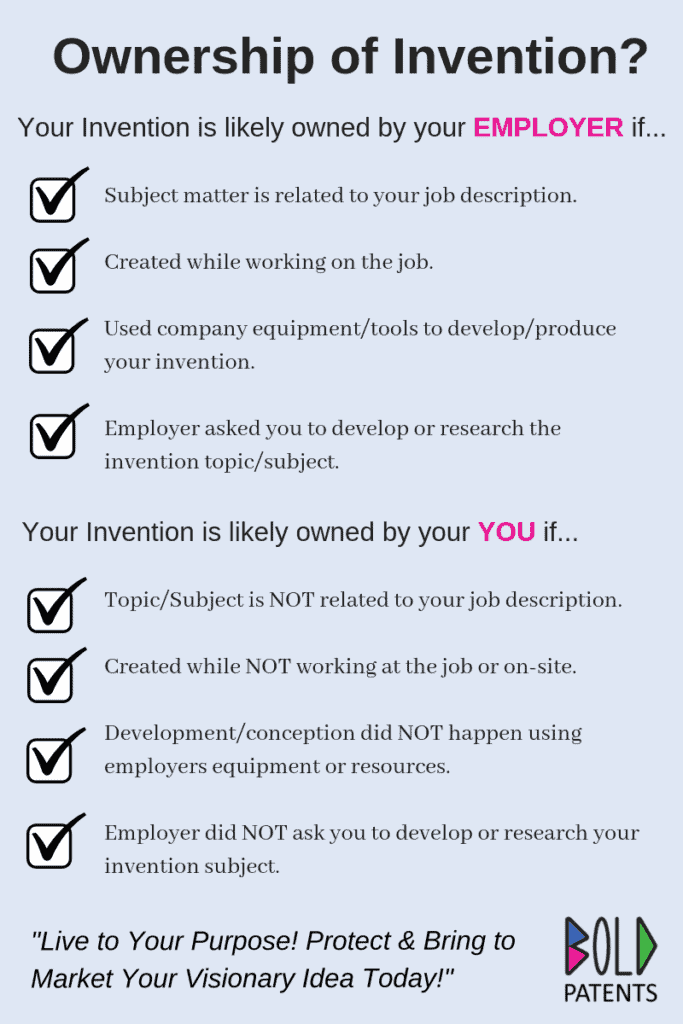

2. Ownership – Who has Ownership?

It becomes critical to understand if you as the inventor are either:

- Inventing on behalf of the company (if it’s related to your job if you’ve worked on the invention on-hours, using the company’s resources) or…

- If it is more like your own personal invention (not related to your job description, has been worked off hours, not using employer’s equipment/resources).

Your invention is likely owned by your EMPLOYER if…

- Your invention subject matter is related to your job description

- Your invention was created while working on the job

- You used company equipment/tools to develop/produce your invention

- Your employer asked you to develop or research the invention topic/subject

Your invention is likely owned by YOU if…

- Your invention topic/subject is not related to your job description/responsibilities

- The invention was not created while on work hours or on-site

- The development/conception work did not happen on employer’s equipment

- Your employer didn’t ask you to develop or research your invention subject

This inquiry can be quite detailed and opinion on invention ownership can be an important thing to discuss with your local state-barred Patent Attorney. (Click here to book your free consultation)

Infographic Explaining Inventor Ownership

Step 4: What Are Your Goals for Inventing?

(CH1 – Prep Work)

Before jumping head-first into a patent project, it is very important to take some time to make sure that the ends will justify the means. In other words, what are your goals? For most entrepreneurs, it is to make money!

I love the “Seeing the forest from the trees” analogy.

In order to see this big-picture, an inventor must remove themselves from the functions and performance and details of their invention (the tree) and zoom way back so that they can see the opportunity (or lack thereof) from a commercial point of view (the forest) before they continue pursuing the solution.

There are many patent eligible, novel, and non-obvious inventions out there that have been pursued, but without a forest-view.

Meaning, the market size and opportunity wasn’t worth the time and/or monetary investment into seeking patent protection in the first place. In other words, had those inventors actually thought about how much they could possibly make if their product sold to as many potential customers as there are, will they make the return they are looking for?

For many inventions (and those we’ve likely seen on the As-Seen-On-TV ads) the answer is no.

…Now, in a very candid analysis, the people that did get paid on those ventures were the attorneys! Don’t you all just LOVE your attorney so much you want to make them rich?

…Didn’t think so 🙂

The attorneys got their legal bills paid, to help them research, draft and prosecute the patent claims through the USPTO (note that average cost to prosecute a patent average well over $25,000).

The moral here is to not let the Patent Attorney be the only one that profits from innovation.

Also, here’s a video that goes through just one way to monetize your invention through licensing… have a look.

But what is your goal? For most entrepreneurs, it’s to make money! So, if the goal for a majority of inventors is to make money, the question becomes…

“…Will you make a reasonable return on your investment?”

Otherwise, the entire venture is a waste.

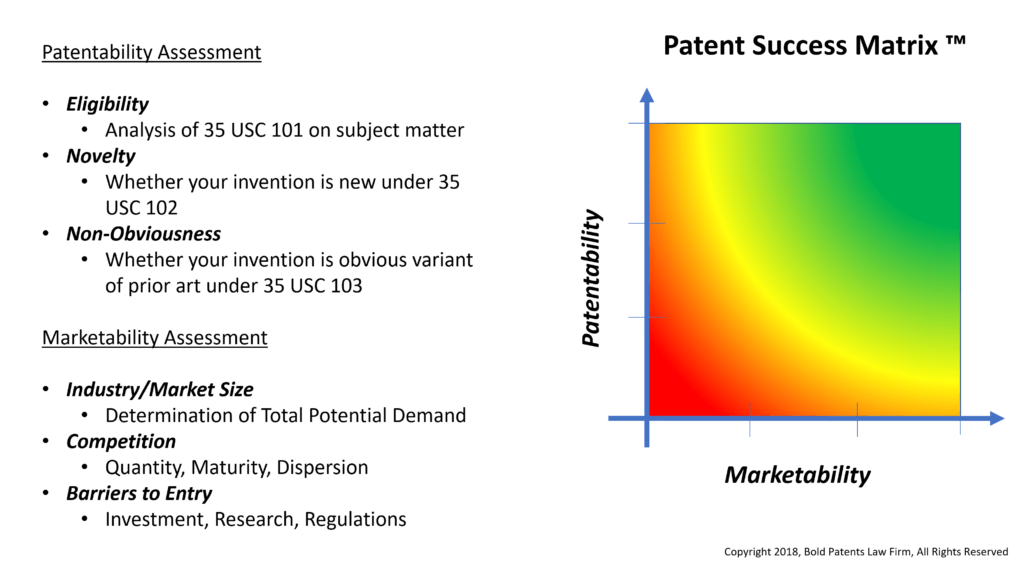

Here is a great chart that should help enlighten you on the BIG upside of market analysis and developing a business plan for your invention.

(Explained in more depth in Chapter 2, Step 7 Below)

Additional Resources:

- A book called One Simple Idea by Stephen Key

Step 5: Are you Barred from Patenting?

(CH1 – Prep Work)

This may not come as a surprise to seasoned professionals that know IP is key to competing at the highest levels, but for many newbies and especially millennials – they grew up on a notion of sharing, open-source, and crowd-funding, and grants for patents.

As you will see below, if you disclose your invention to the public in the wrong way, prior to filing your patent application you stand to lose the ability to claim your invention for yourself – you’ve given it to the public, without any recourse for monetary gain.

The United States’ patent statute provides a one-year limited grace period for inventors to have published their invention before it becomes dedicated to the public domain. This means that if you publish your invention (take it to a trade show, put it on Kickstarter, pitch your business and technology at an angel convention, etc.) you’ve started that one-year timer.

Each country has its own rules about whether disclosure prior to patent filing is permissible.

Be wary of publishing your invention in a trade journal, a show, or presenting it to a panel of sharks, etc. you’ve potentially lost rights in many countries to have exclusivity to make, use, and sell there.

Another trigger that can start the one-year grace period is called an “on-sale” activity.

Whenever you make a sale, or even offer to sell your patented product or service, that TOO starts the one-year grace period in the US and may cause you to lose rights in other countries.

There is a saving grace to this situation…

Confidentiality Agreements

This is a contract, much like any other contract, and it should be taken quite seriously, and an attorney should be hired to assure that it will be binding and enforceable on all parties who are signatures on it.

A major downside to the Confidentiality Agreement (also called a Nondisclosure Agreement or NDA) is that you’re relying on a contract to save your invention.

If the other party breaches the contract and shares your invention with someone else – your only recourse is to fight the legal battle to enforce your contract…and now you’ve lost precious time and resources toward what you really should be focused on: learning how to write a patent application and getting it filed and protected!

The real answer to this is…

File your Patent Application

Instead of relying on an NDA to protect your interest and confidentiality, unless it’s absolutely required to bring someone else into the project for funding, or additional technical consideration – you should work with a registered USPTO Patent Attorney to get your patent application filed, to get your all-important FILING DATE. Then, you can share your invention with anyone and everyone without any worry about confidentiality.

That’s the real beauty of filing a patent application is that you are “patent pending,” and it relieves the inventor of having to worry about showing all of their cards.

Don’t Go Crazy. Share Only what was Filed.

You must only disclose to 3rd parties what you filed in the patent application.

This means that any improvements you’ve come across, any potential new applications, or alternative embodiments you have come across in user studies, or feedback from customers must remain confidential.

You should treat each improvement (no matter how subtle) as close to your chest as a new invention (because it may very well be).

The way patents are monetized is by enforcing them, and the best way to enforce a technology is not with just one patent, but with a portfolio of patents that cover a broad area/swath of the industry and market.

Doing this is a painstaking process which is why you need a patent attorney.

Chapter 2: Patent Search

At this point you understand the difference between an idea and invention, realize your idea is patentable, determine the inventorship & ownership, developed goals, and hopefully, you learned you are not barred from patenting.

Now it is time to do both a patent search and market analysis to determine both the patentability and marketability of your idea.

A patent search is a process for researching the database of existing patents to ensure your invention doesn’t already exist.

A patent search helps you save both time and money by learning early on if your idea is worth pursuing.

I recommend doing a patent search by yourself first (I provided a guide for you below) then after doing your due diligence, book a free consultation so an attorney can do a professional search.

- Blog Article: How to Perform a Patent Search in 6-Steps (The Definite Guide)

- Blog Article: Advanced Guide to Google Patent Searching

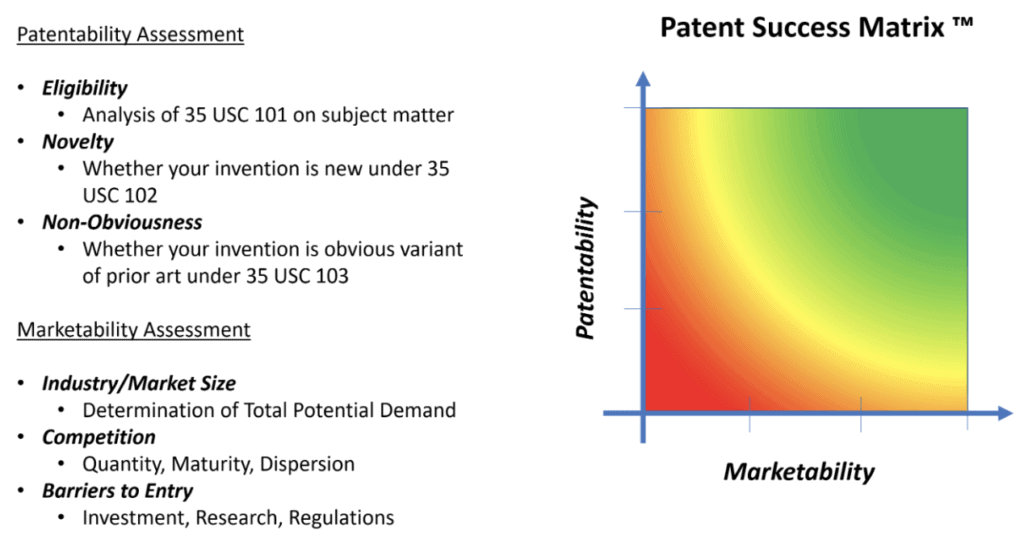

Step 6: The Patent Success Matrix – Patentability & Search Basics

(CH2 – Patent Search)

We briefly talked about the patent success matrix in step 4 on how to patent your idea.

Here we dive into it even further to further emphasize the importance of having a plan in place for making a return on investment.

I tell inventors that simply having a patent granted does not bring you money – you have to go to the market and make it happen.

The lightbulb in the inventor’s eye doesn’t really go off until I show them the matrix.

The Patent Success Matrix was created to help these inventors, entrepreneurs, and business owners see that marketability (the economic viability) is just as important as the patentability (the ability to get a patent often determined by the patent search) when it comes to having a successful invention.

The patent success matrix is composed of two areas. One focused on the patentability of your invention and the other focused on how it will perform in the market. Both areas are needed for a successful invention.

For this step, we will focus on patentability or search. In step 7 we will shift our focus to marketability.

Patentability Analysis Explanation:

The first axis of the Patent Success Matrix is Patentability or often called the Patent Search, which is the likelihood that your invention will become a granted patent. It measures the degree to which the invention is novel (new) and nonobvious (different) as compared to other innovations in the same industry.

There are three big considerations to make under this patentability analysis.

- Eligibility (35 USC 101). We’ve discussed eligibility above, and this weighs higher for those inventions that have very little if any risk to being assessed as “abstract ideas.”

- Novelty (35 USC 102) which assess how new your invention is as compared to the prior art.

- Non-obviousness (35 USC 103) assesses whether your invention is an obvious variant of prior art. The more eligible, novel, and non-obvious, the higher the score will be on the vertical (patentability) axis.

Let’s dive into each of these areas in more depth.

1. Eligibility:

This is where you must start the analysis! Many inventors and even patent Attorneys forget to stop here first (before patentability) and confirm subject matter eligibility before anything else.

I recently wrote an article specifically on eligibility (3 Steps to Patent Eligibility article). I’ll keep it brief here.

BOLD TIP: For an excellent article dedicated to answering this question “Is my patent eligible?” read here.

The thing to know is that there are 5 categories of an invention that the courts and the USPTO have deemed to NOT be patent-eligible:

- Laws of Nature

- Organization of Human Activity

- Natural Phenomena

- Mathematical Concepts

- Mental Processes

Now… even if your invention could arguably fall into one of these categories, the latest 2019 guidance provides not one but TWO ways in which your invention may still be eligible:

- If the invention is directed to a practical application

- It has an inventive concept and is no obvious as compared to the prior art

2. Novelty: Is your Invention New?

This is THE biggest question in patent law. It’s the simplest, and most straightforward part of the law and most everyone I talk with gets it right away.

In order to get a 20-year patent for your invention, you need to convince a USPTO examiner (that by the way looks at inventions of your type all day every day) that you’re the FIRST EVER, in the WORLD.

Don’t be scared. As we mentioned above, the inquiry that the examiner is going to make is not whether EVERYTHING we describe in the specification and drawings is the first-ever in the world – but instead, they will be looking at the CLAIMS of the invention to see whether what you are claiming is the first-ever in the world and that no one has ever done it before.

The USPTO examiner is assigned to a single art-unit. Art units are broken up into very specific different areas of technology. These examiners only review patent applications within a specific art unit.

They are trained at colleges/universities just like engineers or scientists are and then they are trained in the Manual of Patent Examination Procedure (MPEP) and (just like Patent Attorneys) they have to take and pass the daunting Patent Bar Examination. They know their stuff.

They know their field of technology so well, they know what applications are pending in foreign countries, the state of the art in general and even what problems are unsolved in the industry.

Your patent attorney is here to help. Crafting claim language is likely the most difficult thing to do with the English language. It’s the Patent Attorney’s responsibility to attempt to carve out in precise fashion what the inventor has created, and help it stand out as new/different from the state of the art as it is today.

3. Nonobviousness: Is my invention an obvious version of something else?

Don’t over-think this word. It simply means that the examiner must not think that your invention is just an obvious variation/version of something else that exists in present-day technology. This is just one step of the process that usually follows the novelty analysis.

The inquiry is that even if your invention is novel, and the examiner can’t find anything exactly like what you’ve claimed, if what you’ve claimed is an obvious iteration or variation of something else that’s already published, you will not get a patent granted.

Thus, you need to show the examiner in that case, that a person of ordinary skill in the technology would not have known to combine elements A and B, and that there was nothing to point to the combination of A and B.

How a Patent Search is Conducted

When conducting a patent search you use a variety of online tools provided by Google, the USPTO, and other third parties to research and determine the patentability of your invention.

Once again, this process can be a bit complicated and making the wrong move can cost you quite a bit of time and money.

I highly recommend you seek legal help. Click here to book a free consultation if you would like to work with us.

It would be our honor to help bring your visionary idea to reality!

Step 7: The Patent Success Matrix: Marketability Analysis

(CH2 – Patent Search)

Now that you clearly understand what it takes to have patentability and have performed a search here are three indices that make up the overall marketability score:

- Industry and size: Quantify/predict the demand for the product/service.

- Level of competition in the market: Wee how many competitors there are, how mature they are and how spread out they are.

- Marketability analysis: Barriers to entry – which are legal, financial, governmental or credential-based barriers to getting started.

The larger the size of the market, the fewer competitors, the lower the barriers to entry, the higher the marketability score will be.

Gaining a clear understanding of your market size, addressable market, and target market will help you and your team realize the true potential revenue that your innovation could bring.

Market Research

While these types of research projects are never going to be guaranteed predictors of the future, they will help you the inventor make a very informed decision on whether to pull the trigger on spending time/money on a patent for your invention.

Working closely with someone who can help you predict revenue 3 or even 5 years down the road will help you build a strategy around cost structure so that you don’t go out of business before your product hits the market.

One of the most important aspects of our jobs as attorneys is an ethical and moral obligation to help our clients succeed. Success can be defined in many ways, but in terms of dollars, we want our clients to be able to be commercially viable, making profits and most of all creating positive change in the world.

The whole point of inventing and publicizing your creations is so that we as a country and a world get smarter every day and help make each other’s lives safer, more efficient, and more enjoyable through innovations.

There is Too Much Risk, I’m Not Willing to Seek a Patent, Now What?

If after doing the hard work, and conducting Market Research, and after talking with your Patent Attorney, you decide that there is too much risk to go down the patent protection route (either based on legal/eligibility challenge or financial/market outlook), there are still alternatives for you to choose.

Protecting your innovations with trade secret protections is a great place to start.

Trade secret law is closely tied with employment law, and in summary, helps to prevent unauthorized disclosure of your company’s valuable information to third parties or the public at large. Trade secrets allow your company to have and maintain a competitive edge if the trade secret remains within your company.

There is work that needs to be done to keep trade secret status. But, remember, there is not a certificate or registration of a trade secret by any government body, only the ability to meritoriously sue someone who takes (misappropriates) your trade secret information.

Trade Secrets

Trade secret law is governed by each state; however, each state has adopted the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA) as part of its statute. In addition, in 2016, the Defend Trade Secrets Act (DTSA) was adopted to provide for a federal remedy in federal court to address the sprawling nature of companies that exist in multiple states and employ many people across the country (if not the world).

To enforce your company’s trade secret rights, you must show three elements:

- The Trade Secret information must not be readily ascertainable (meaning not known in the public)

- The Trade Secret information must be actively kept a secret (modern encryption software, locks, access permissions, etc.)

- The Trade Secret information must be valuable to the company (usually shown by demonstrating the immediate value to a competitor)

There is a lot of power in trade secret protection.

One of the key insights here is that the duration of protection for a trade secret is theoretically in perpetuity (without end!), if the secret remains valuable, not known by the public, and efforts are being made to keep the secret – you can protect your innovations well beyond the 20 years that Patent Law affords you.

Helpful Links:

- Blog Article: Trade Secrets – Knowing When to Keep Them

- Blog Article: Patents v. Trade Secrets

Chapter 3: Filing Your Patent

If you completed your patent search and it is time to file your patent!

Before you get to filing it’s a good idea to understand the different applications, costs, and timelines you can expect. Although I won’t be able to go over all of this in this article I will make sure to link to other useful resources to ensure you have everything you need to bring your visionary idea to life!

It’s time to live to your purpose by protecting and bringing to market your visionary idea.

#improveourworld

Step 8- Filing your Patent Application (What are They? Which One?)

(CH3 – Filing Your Patent)

Filing the right application with the right information

There are a lot of different types of patent applications available for inventors. What’s nice is that there are some common threads that are true no matter what, and they are:

- The invention must be novel and non-obvious (as discussed above in chapter 2).

- Only one patent will issue for each invention.

- When you have been given patent rights, you can prevent others from making, using, or selling your invention.

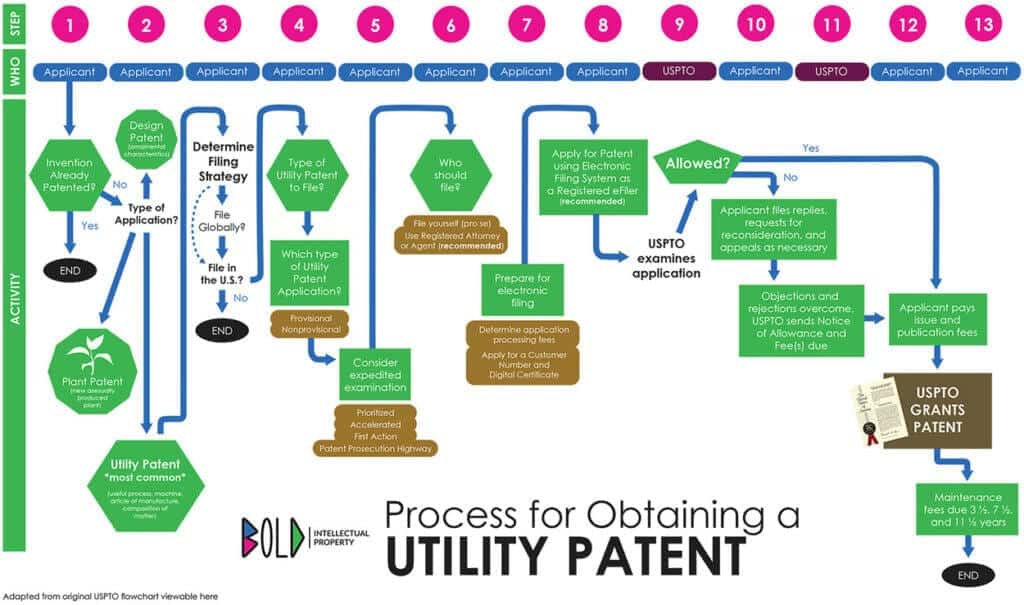

Below I have provided a graph that shows you the process.

Please Note: A utility patent means the same thing as a non-provisional patent application (NPA).

Provisional Patent Application

A provisional patent application is an informal application that serves to preserve a filing date for an invention that must be followed up by a nonprovisional patent application within one year.

After you file a provisional application you enter patent-pending status. (Blog Article: What Does Patent Pending Mean?)

The provisional application will contain a specification and drawings, but usually not a claim set.

The beauty of a provisional is that it allows the inventor time to develop prototypes, take their invention to market and explore customer feedback before locking in the all-important claims of the patent application. A provisional application, by preserving the filing date, allows an inventor to legally state their invention is patent pending.

The America Invents Act of 2013 turned our country from a first-to-invent system to a first-to-file system. That means that it’s a literal race to see which inventor files the invention first (Assuming more than one inventor has the same/similar invention at the same time).

If you are interested in learning more about how to go about filing a provisional patent application check out the video or resources below!

Nonprovisional Patent Application

This is the formal application that gets submitted and examined by the United States Patent and Trademark Office USPTO.

The application is formal because it must have specific sections within the specification and must have a properly formatted claim set.

In addition, it must have drawings with proper formatting.

On top of the rigorous requirements for formality, a nonprovisional patent application must be submitted with a large stack of paperwork comprising an oath/declaration, invention disclosure statement, and an application data sheet. These documents will be outlined and explained in detail by your patent attorney or paralegal.

The Nonprovisional Application is the basis for all follow-on applications that we’re going to discuss later including divisional, continuations, and international patent applications.

Additional Information:

Divisional Patent Application

These types of applications must come after a Nonprovisional patent application – and usually come as the result of a restriction requirement office action.

When the patent office receives an application, one of the first things they will do is evaluate whether there are multiple inventions within the one claim set filed for.

Often times, the attorney submits a large claim set covering many different aspects of the invention – and in some cases, those are so different, that the examiner sees them as two or more patentably distinct subjects.

The rule is that you are only allowed ONE patent for ONE invention. It seems obvious, but many inventors forget about this when they submit their claims.

Continuation Application

These applications are for those inventors that just can’t keep from, well… INVENTING (and re-inventing)! In other words, they have found improvements on their originally filed invention, and want to separately protect those improvements (bells & whistles I call it).

As long as those bells and whistles (improvements) to the base invention were described at least in part in the base nonprovisional filing, then you can file what is called a continuation or ‘continuation in part’ patent application.

This is THE key way to build a patent portfolio.

A patent portfolio is a fancy term for more than one patent. If you go to try to license or sell your invention, a buyer or licensee will want to see that you have more than one claim set that covers your invention – it spreads out the potential infringing net and strengthens the overall schema.

The more claims and patents you have in your portfolio, generally, the more powerful and more difficult it will be to get around (by a competitor).

Additional Information:

Design Patent Application

Very different from utility patent applications, design patent applications seek to protect purely the 3-dimensional SHAPE or ornamental appearance of the object/product/device.

Design patents (if granted) provide exclusive rights for only 14 years from the day of filing as opposed to 20 years for their utility counterparts.

You can do BOTH!

Yes, you can (and for most hardware/devices you SHOULD) seek protection for both the utility – which protects the functionality and the design – which protects the way it looks.

Watch the video below to learn more about how to patent a design patent or click on my resource to get a better understanding of the filling process.

- Blog Article: How to Easily File a Design Patent in 10-Steps

Plant Patents

These are quite rare, not necessarily because they are hard to acquire, but there is just less innovation in plants and botany.

The requirements for getting a plant patent are still the same for utility patents, although the major difference is that the eligibility only requires that they be non-tuber and asexually reproducible.

Don’t get weirded out by that – it just means that the plant must be able to be propagated in a lab-setting without the use of pollination (or nature) to procreate. Grafting, bonding, or otherwise combining plant tissue to form repeatable functional, and beneficial results through plants is patentable.

Genetically modified and/or genetically engineered foods are prime examples of potentially patentable plants or seeds.

Watch the video below to learn more about how to patent a plant patent or click on my resource to get a better understanding of the filling process.

- Blog Article: How to file a plant patent in 5-steps

Step 9: International Patent Applications

(CH3 – Filing Your Patent)

International Patent Application

This is such an important topic – as many inventors overlook this, or even yet, don’t know to ask about it.

When seeking patent protection from the USPTO, you can’t forget that it is only the “US” that you’re seeking rights for.

You should definitely consider getting patent protection in all countries that have a market demand for your product.

In some rare cases, US inventors (after doing a thorough marketability study) will actually be wise to seek patent protection in countries other than the US as that is where the customers are!

An international application that is common to use if the inventor is going to see protection in more than 3 countries is the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT). This treaty allows the inventor up to 30 months to decide which foreign countries they want to file into while their US patent is pending.

The PCT also allows the inventor to save time/money by not having to pay for and wait for the patent search to come back from each country – instead, they will ALL recognize the US examiner’s search.

Learn how to expedite an international patent filing by watching the video below.

Additional Information:

Chapter 4: Post Filing

At this point, you know how to patent a product and you have completed your patent application. Now are waiting patiently for the prosecutor’s decision.

You may be wondering, how long does it take to get a patent? What are the costs involved?

It depends on so many factors. An example would be poorly written applications which results in a long time to examine and understand the language of the patent you are trying to protect.

That is why it is recommended that you do not file a patent yourself, and let a professional patent attorney file it for you.

If you want to dig deeper I provided you with additional information below.

- Blog Article: How much does a patent cost?

- Blog Article: How long does it take to get a patent?

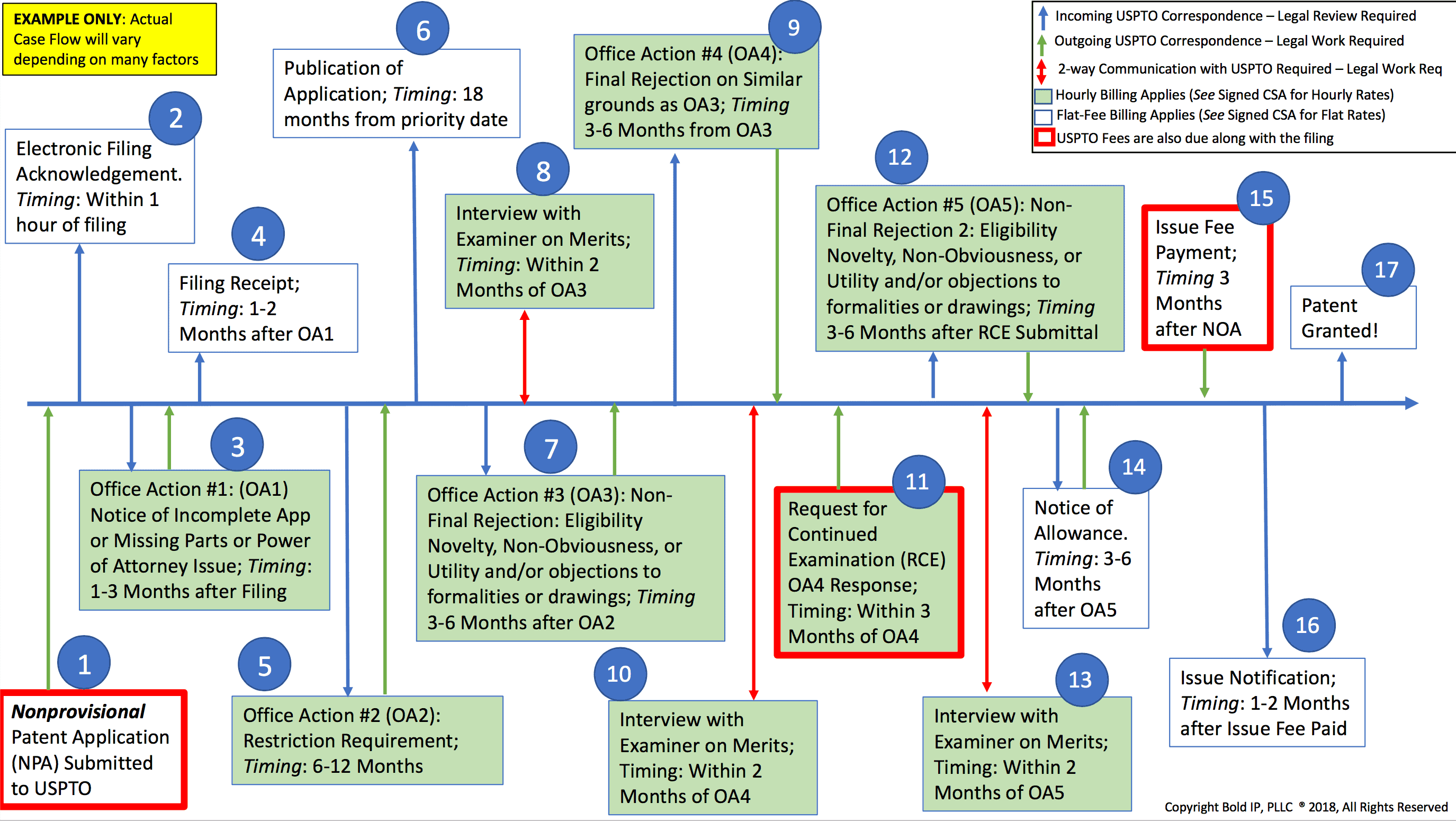

Below, I have also provided you a flow chart that gives you a general idea of some post-filing procedures and when to expect them. I will do my best to reference the items as I go through the final steps of the “How to Patent an Idea” blog article.

Step 10: Patent Prosecution: Office Actions

(CH4 – Post Filing)

Knowing how to Navigate the Examiners and USPTO

As soon as the application is filed, there are multiple eyes that see the spec, claims, and drawings and decide on which art unit to send it to. There are around 10 different art units and it is important only so much that it will determine who the examiner is that will be assigned to the invention.

Once you get assigned an examiner – you are stuck with them, for better or worse.

Office Actions

This term reflects any and all correspondence that may be received from the USPTO after submitting the patent application. These office actions can be anything from merely procedural typo corrections to substantive rejections or objections.

The most common first office action is a restriction requirement office action – this means that the examiner sees that there is actually more than one invention in the claim set.

This can be a good thing!

A response can be as simple as electing the main embodiment of your invention, and then filing a divisional application to cover the remainder – more on divisionals later.

Typical office actions that are “on the merits” are those that you really need to watch out for. These rejections, objections, or allowances are the results that come after an examiner has done their own searching, and has come up with their determination on whether they will allow the patent application to go through to issuance.

It is typical to get at least one rejection – so don’t be saddened if your patent application gets a non-final or even a final office action. They are in most cases, able to be overcome with some combination of legal arguments or amendments.

Watch the video below to learn more about patent office actions.

Examiner Interviews

There’s nothing like being face to face (or at least ear-to-ear – if over the phone) with the examiner. So much in today’s world (including the patent office) is done through electronic communication, email, and exchanges that lack the human quality.

An interview can make up SO much ground, where there may have been some emotion growing on either side, a personal human conversation can smooth all of that out.

It’s great to know that an examiner’s job is to simply apply the rules the patent office passes down. A level-headed, objective approach to working with them is always going to win the day versus an adversarial, judgmental and emotional approach.

Step 11: Escalation – Petitions and Appeals

(CH4 – Post Filing)

Petitions and Appeals

It happens. Sometimes, examiners just don’t see eye-to-eye with inventors and their attorneys. And because of a technical or process reason, there is a need to escalate the examination to a higher authority.

However, most petitions are process-based and have pre-designed objectives whether it is for moving up the application (an example is making an application special based on the age of the inventor, or other circumstance), or allowing certain exceptions to rules that are out of the hands of the individual examiner.

Petitions serve just this purpose. By petitioning to the art-unit director – the inventor is able to achieve at least another set of eyes on the legal argument.

In other cases, when the examiner has made an error or substantively disagrees about the novelty, non-obviousness or utility of an invention – the examiner’s decision can be appealed to the patent trial and appeal board (PTAB).

What the video below to better understand the patent trial and appeal board (PTAB).

The PTAB sees patent decisions all day, and the judges on the panel are experts at parsing good from bad legal arguments against examiners. While it is rare, appeals can serve to help inventors get patent rights, where the examiner would have rejected them.

Step 12: Creating Portfolios: Divisional and Continuation Applications

(CH4 – Post Filing)

Building a Patent Portfolio During Prosecution

While a patent is still pending, a portfolio can (and should) be created. The primary way, as mentioned before is by creating at least one or more divisional applications when there is a restriction requirement separating claim sets.

Another great way to create additional parallel patents covering technology is to file continuation applications when the inventor has improvements on their invention that come up after filing the original nonprovisional patent application.

These continuations will stand on their own, and the improvements need to be substantial enough so that they will not be simply considered obvious variants of the underlying nonprovisional application.

Both divisional and continuation applications will undergo separate examination (not necessarily by the same examiner – but usually they are). And have completely separate issue dates and authority for claiming/allowing.

Step 13: Patent Granted!

Notice of Allowance and Patent Granted: You made it!

Once you respond to the last office action and the examiner is satisfied, they will send back what is called a Notice of Allowance, and that is when the champagne bottles should pop! You’ve been told by the patent office that your invention is worthy of being granted.

The reason why they provide you notice of allowance is to give you a chance to file those continuation applications to complete the patent portfolio. It’s your last call to submit any other improvements or variations that were not covered by the base invention.

After you pay your issue fee, the USPTO will GRANT YOUR PATENT RIGHTS! They will send you a hard ribbon copy of your patent, as granted and provide you with the official patent number and date.

What’s Next?

There is so much more to come after you’ve received your patent – we will save that for another blog article (or two).

Follow These 13-Steps To Get a Patent For Your Idea

Remember that ideas are a dime-a-dozen. It’s your courage to take the idea to the next level by knowing how to patent a product that makes you stand out from the rest of the inventors.

Follow these 13-steps to protect and bring to market your visionary idea:

- Do you have an idea or invention?

- Is your patent eligible?

- Determine who the inventors are and who will own it.

- What are your goals?

- Are you barred from patenting?

- Patent success matrix – patentability

- Patent success matrix – marketability

- Filing your patent application

- International Patent Applications

- Patent Prosecution: Office Actions

- Escalation: Petitions & Appeals

- Creating Portfolios: Divisional and Continuation Applications.

- Patent Granted!

Because you are up for the challenge, I encourage you to book a free consultation with us where we will also provide you with our Bold Patents The Inventor’s Guide to Patents book free of charge! (Click here to get started today!)

What did you think of the article? What questions do you have about protecting and bringing to market your visionary idea? Please let me know in the comments below! I am here to help!

—

Legal Note: This blog article does not constitute as legal advice. Although the article was written by a licensed USPTO patent attorney there are many factors and complexities that come into patenting an idea. We recommend you consult a lawyer if you want legal advice for your particular situation. No attorney-client or confidential relationship exists by simply reading and applying the steps stated in this blog article.