This is a very good (and properly worded) question. The answer is, of course, maybe.

And it’s usually followed by a “Well, tell me about your invention….”

Actually, more often than not, I hear the question asked as, “Can I get a patent on that?”

In fact, I’ve heard this question asked so many times that I decided to start a series of coffee chats here locally in Seattle where I meet with inventors and entrepreneurs from around the community 3 days a month.

I have utilized the Meetup.com platform (which I love, by the way). I have called the Meetups: “Can You Patent That? Coffee Chat.”

I have one on the Eastside, Northend, and Downtown for any readers that are local. Let’s talk patents over coffee! But, shhhh… we gotta keep it all high-level — nothing confidential!

And that is actually the second real step to finding out whether your invention is patent eligible: disclosing your invention to your patent attorney. But more on that later on.

I’m going to go through the 3 steps here in this article and provide you with valuable information and helpful tips along the way related to how you can—and should—take action.

Step 1: Is your invention really yours?

The answer here, if we’re being honest, is almost always no. That’s because, as an inventor, you know what you know based on the years of research, findings, discoveries, and inventions of those that came before you.

As an inventor, you seek to make the world better through improving the world around you.

And yes, that means that you owe a debt of gratitude — as we all do — to the hardworking men and women in the profession in which we now find ourselves.

All that aside, what’s key here is to think about invention ownership, inventorship, and initial disclosure rules. Let’s take them in turn:

Invention ownership is important when an inventor works as an employee and the invention can be argued to have been created or conceived while on the job. Some employers are more aggressive than others, but this is a huge point.

If your boss or supervisor has asked you to come up with a solution to the problem for which “your” invention solves — and especially if you were working on hours as you (even in part) conceived of it — it’s likely going to be owned by your employer, not you.

I know — bummer, right? However, it’s better to know this right up front! So make sure to invent off the clock, in a subject matter unrelated to your job description and without using company resources (computer, phone, equipment) if you really want your invention to be, well, yours.

I will caveat this by saying that every state has their own employment laws on the books, and to be certain (if there’s any ambiguity), it’s important to speak with a locally-barred employment law attorney.

Now, on to inventorship, which is just as important as ownership to get a grip on right up front. Naming and coordinating with any and all co-inventors is critical to the patent process. If you have conceived of your invention (even in a small way) along with another inventor or inventors, you need to be naming them as co-inventors as the invention proceeds.

Co-inventors of a patent are given special rights, similar to a joint-tenancy in real estate law. They have unfettered rights to make, use, sell, or import the invention without need to seek permission from the other co-inventors.

While a patent application is drafted and prosecuted (meaning argued before the USPTO patent examiners), having all co-inventors participate is required. Trying to modify a patent after issuance or grant will take a re-issuance of the patent and a lot of cost and expense as well as a requirement to show that not naming the co-inventor on the original application was not done so by intention to deceive, mislead, or defraud the USPTO.

As we’ve talked about in prior sessions, statutory bars are so important to consider when starting the patent process. These rules will make or break patents.

It’s sad but often true: most issues don’t arise until way later and the patent-holder is asserting the patent rights against infringers — and the infringer finds out they broke these rules — and the whole patent gets invalidated, or thrown-out.

So don’t let that happen to you!

The 1-year “on-sale” bar prevents any inventor from filing a patent application for any subject matter that was on sale more than 1 year prior to filing! Just recently, the Supreme Court decided that even secret offers to sell the patented product would start the 1-year period.

The 1-year “disclosure” bar prevents any inventor from filing a patent application for any subject matter that was disclosed to the public more than 1 year prior to filing! This means that if the information was findable by someone in your field of invention, it’s arguably going to be declared a dedication to the public, owned by the world, not you.

Bottom line: If you want to protect your invention with a patent, don’t let 365 nights (or days) go by after disclosing or selling (including even offering it for sale) your invention.

Step 2: Invention Disclosure

Moving on: so you know that your employer doesn’t own the invention (or, possibly, you are the employer! ), you’re aware of any and all co-inventors, and you are cleared on the 1-year statutory bar disclosure and on-sale bars.

Phew! Now, what to do next?

Oh right: let’s talk about your invention.

Before you go talking to just anybody claiming to be a “patent expert”, please do your homework on who you are meeting with.

I wrote a nice article all about what to think about when first meeting a patent attorney. So I’ll spare you the details and let you read up there. I cover the bases from how to look them up to making sure they are legitimate, and some of that common sense stuff, like making sure you connect and get along.

Assuming you’ve made the bold choice, and found the patent attorney for you (hint, hint), it’s now time to make sure your attorney knows about your invention in great detail.

Making your patent attorney understand your invention is a great start, but it is far from the end. They will — they should — look to have you disclose any other embodiments that are feasible or possible, and ideally push you a bit to further explain what could be and get down to the details.

Disclosing your invention for all it is and could be is very important to do so that the attorney can evaluate and assess the entire invention before determining eligibility.

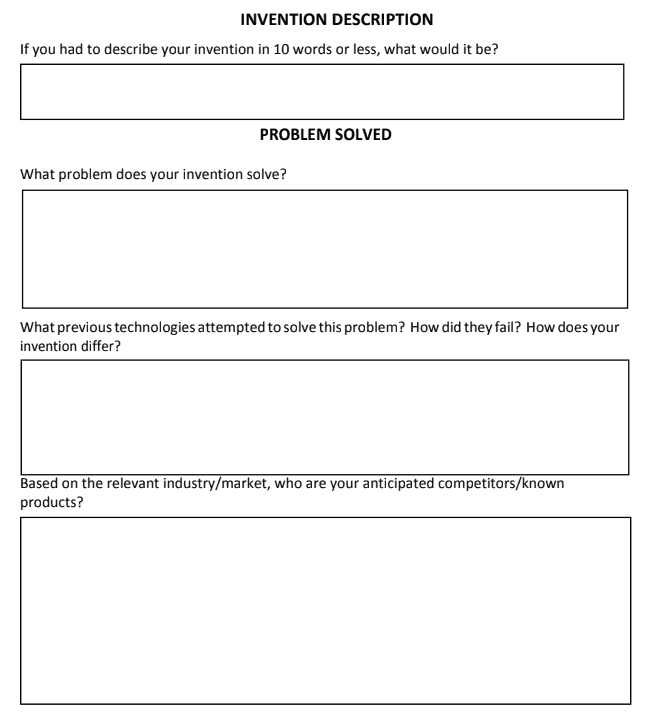

Most patent attorneys will do some sort of intake process and provide you with a guided approach to disclosing your invention and pulling out the detail. This is preferred to the free-for-all approach, as some critical features or aspects of your invention may not get teased out.

Below, you’ll find some excerpts of our Invention Disclosure Form, which we ask inventors to fill out as part of the first thing they do when they become a Bold client.

Once your invention is fully disclosed, your patent attorney will then apply the latest guidance from law, court rules, and USPTO guidance to make a decision and provide for you a legal opinion on eligibility.

Step 3: Patent Eligibility

I don’t plan to replicate the amazing content that is already on the USPTO.gov website governing patent subject-matter eligibility. There are a lot of great comments, articles, and discussions on this all throughout the World Wide Web too.

In my humble opinion, if I were to point you to some authoritative sources on point, here is a short list:

- USPTO.gov website

- 2019 Proposed Rules

- Full Chart on All Subsections Changed in 2100 (Warning: Only for brave souls!)

- MPEP 2100

The basis of Patent Subject Matter Eligibility starts with the landmark case of Alice v. CLS Bank (Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 573 U.S. 208, 217-18 (2014) (citing Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012)).

This case struck down a patent that basically conducted currency exchange using a computer, and the Supreme Court said that this type of invention is abstract and invalid under patent law. It started a multi-step approach to analyzing whether certain subject matter is patent eligible, as shown below:

To be patentable, an invention must be directed to patentable subject matter (§ 101), useful (§ 101), novel (§ 102), and non-obvious (§ 103) in light of existing technology and knowledge (referred to as “prior art”).

Patentable subject matter as defined in 35 U.S.C. § 101 states:

Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvements thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.

Thus, four categories of patentable subject matter exist: (1) machine, (2) manufacture, (3) composition of matter, and (4) process.

This may seem to cover everything under the sun, but the Supreme Court has long held that several exceptions are innate to these classifications.

The law surrounding judicial exceptions for subject matter that has been identified as the “basic tools of scientific and technological work” remains in flux; however, the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance (“Guidance”) now employs a two-prong inquiry in order to determine whether claimed subject matter is eligible for patentability.

So: what’s considered abstract and not eligible?

Well, it’s a 2-pronged analysis…

Prong One:

The 2019 USPTO Guidance provides that the judicial exception for abstract ideas can be classified and directed to:

- Mathematical concepts

- Methods for organizing human activities

- Mental processes

- Laws of nature, and

- Natural phenomena.

Your patent attorney may need to assess recent Federal Circuit, Supreme Court, and District court cases to make a determination for your specific invention and the applicable judicial exceptions.

If the invention is not directed to one of these five areas, then the invention is eligible. Woo-hoo!!

If your invention is on the fence, or you’re not sure, then the analysis will continue.

Prong Two:

Under the second prong, it must be determined whether the claim provides elements, in addition to the judicial exception, sufficient to integrate the judicial exception into a practical application.

Note: A judicial exception may be sufficiently integrated if the practical application applies a “meaningful limit” to the exception.

Even if there is arguably no “practical application” that can be shown, there is still hope if there’s an “inventive concept.”

But… what’s an inventive concept?

In order to be considered an inventive concept, the element(s) must “amount to significantly more than the exception itself.”

This means that there is an element (or there are multiple elements) that “add[s] a specific limitation or combination of limitations that are not well-understood, routine, conventional activity in the field.”

If an inventive concept can be demonstrated, the claim may be eligible for patentability.

So, there you go: clear as crystal, right? I know, I know — it’s a little complicated. But that’s why there are patent attorneys who can help you navigate through this spaghetti noodle of analysis.

So… what’s next?

Now that your invention is eligible for patent protection, you need to see whether your invention is patentable!

Patentability for utility (or functional) inventions comprises:

- Novelty

- Nonobviousness

- Utility

You’ve got to be the first in the world to claim the subject matter (novelty), and not disclose or claim an obvious version or variant of something from the prior art (nonobvious) and have real-world benefit (utility).

If you’re at the stage and want to read on about what it takes to conduct a patent search, I wrote a recent blog post all about it here.

In Conclusion…

As you can see, eligibility isn’t an easy answer to find! We hope this post gave you some more information on patent eligibility and you feel more confident moving forward with your own invention. Remember the following three steps when determining if your patent is eligible.

- Is your invention really yours?

- Invention Disclosure

- Determine Patent Eligibility

As always, remember that there is a lot of work that you can and should do on your own before hiring a patent attorney to do a professional search and give you their opinion on patentability. The article on how to do a patent search will be a great start.

And if you’re really just getting started, you should schedule to speak to a patent attorney today to get a sense as to the process and figure out what information will be needed to get the ball rolling.

Tell us: what did you learn about patent eligibility when reading this article? Did you figure out whether or not your invention is eligible for patenting?

Are you ready to move forward with an invention of your own? Don’t wait: book your free consultation with us to get started!

—

Legal Note: This blog article does not constitute as legal advice. Although the article was written by a licensed USPTO patent attorney there are many factors and complexities that come into patenting an idea. We recommend you consult a lawyer if you want legal advice for your particular situation. No attorney-client or confidential relationship exists by simply reading and applying the steps stated in this blog article.