Ah, yes… the financial side of patenting. This may not be the most fun or glamorous, but it is central to planning your patent journey and knowing the key things to expect along the way… after all, it is part of business!

The thing about patent costs is that they can get a little nuanced depending on various things like fees, amendments with examiners, formal drawings, and more.

So, what does this mean for you? What is the cost of a design patent? Today, we are going to dive into that in this ultimate guide to help you answer that question!

Quick Intro

Without getting too far in the weeds of patent-ese (don’t worry, I will later), I wanted to break down for you the quick 1-minute answer. This is for those of you who want the good stuff first or only need the gist of it now:

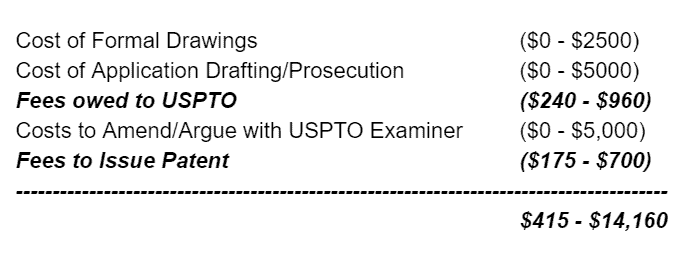

So, as you can tell, the cost varies depending on whether you are going to do the work yourself, or if you’re going to hire professionals (drafters, patent attorneys, etc.) to help you with the design patent filing, prosecution, and issuance processes. With the aid of professional drafters and counsel, costs could be as much as $15,000.

Eesh… that definitely seems like a hefty price tag, especially when you compare it to the basic costs. But, and we can’t stress this enough, having professionals involved is a vital part of the process. No matter how much you learn about IP law, having a knowledgeable patent attorney can genuinely make the difference between a success or a horror story… after all, no one wants to mess up a small detail and end up losing the rights to their idea to another entity forever.

With respect to the USPTO fees (in bold italics), these fees vary depending on whether the applicant qualifies as a “small” or “micro” entity. If the applicant is a business that has fewer than 500 employees, they likely qualify for a small entity and will pay reduced fees. If the applicant has a modest income and has not filed many patents before, they may even qualify as a micro-entity and save even more money.

If you’ve read my other articles on utility patent filings, you’ve probably heard me speak very highly about the virtues of doing a patent search. In the case of design patents, however, I will not say that is so.

The difficulty of actually searching for visual detail/components is nearly impossible (although conceivable with some future-form of technology using Artificial Intelligence).

As I usually do, I think it’s important for all of the readers here to be clear on what the differences are between a utility and a design patent. If you are already sure that what you need is a design patent, then read on for the important financials! Otherwise, feel free to reach out to us and talk through your idea if you are uncertain.

Design patents are a great option for inventors who wish to protect the way their invention looks as opposed to what it does (which is for utility patents). Now, it’s important to note that you don’t have to choose one or the other… you may (and often should) acquire both. NOTE that design patents are only for “articles of manufacture” meaning they have to actually have a 3D shape in order to get a patent on the form.

Why Should you Care about Cost?

You’ve got to plan! If the cost is too much initially, then you need to explore raising money either through friends/family, investors, or securing a loan through a financial institution. There is some risk in exposing your invention to these potential investors and third parties, though. For this reason, always use a Nondisclosure Agreement (NDA), also called a Confidentiality Agreement if you have any doubts or worries.

The risk of disclosing your invention to potential investors, buyers, or clients is that it usually counts as a “publication” and/or “offer to sell”. This triggers a 1-year window from when you first disclose to when you MUST file for a patent application, or else your invention may be later invalidated (deemed public domain) due to the one year lapsing.

As with most projects we take on, it’s important to understand what’s involved with a design patent before starting. The basic steps are:

- Deciding Utility or Design patent

- Design patent search

- Design drawings

- Claim/Description/Abstract

- Application Components

When deciding whether to go utility or design, you’ve got to think about what parts of your invention matter the most or are most unique. Is it the way the invention functions? Or is it the way it looks? If functionality is the primary differentiator, then you should seek utility patent filing. If design/looks are what differentiates, then seek a design patent filing. Both is an option if you can’t decide.

I did spend a good deal of time on this topic of whether to go utility or design, and (as you probably guessed) The basic summary of the article is:

- Utility patents protect an invention for up to 20 years from the date of filing, whereas design patents give 15 years of protection from the date of issuance/grant

- Utility patents protect functionality, whereas design patents protect the way the invention looks

- Utility patents have several (usually 20 or so) written claims that govern the scope of the rights, and design patents only have just 1 written claim and the rights are governed by the drawings

Design patent search

It is critical to know whether it’s worth spending the time and money on a full design patent filing. For a full article on design patent searching, check out our main post. The basics are:

- Determine the structural elements of your three-dimensional invention

- Refine the set of elements down to 3-5 key keywords that summarize the alleged unique shape

- Conduct keyword searching based on the physical elements discussed and shown in your design to confirm/deny novelty and non-obviousness

Of course, the complexity of design patent searches definitely adds more importance to having a quality patent attorney. Be sure to reach out to us so we can help out and make sure everything is thorough!

Drawings

As mentioned before, the heart of a design patent is not the words on the patent, or the claims themselves. It’s all about the drawings. So, it makes sense in almost every scenario to have a patent drafter complete the 2D drawings of the invention.

A patent drafter is usually required because they understand not just the rules (35 USC 171), but how to push the limits a little. This can even sometimes achieve more rights than are deserved in some cases. Much like a Patent Attorney crafts each word of a claim set in a utility patent application, the Patent Draftsman (or woman) approaches each solid line or dashed line with precision.

Depending on how broadly the Patent Attorney overseeing the drafter wants the design application to be, it will change the way the drawing looks and to what degree the environment is pulled into the claimed drawing.

Solid lines are what define the scope of what’s being claimed, whereas dashed/dotted lines are those areas unclaimed. Meaning, the dashed lines/edges/environment could change or take on completely different forms and still be potentially infringing of the design patent if it were to issue.

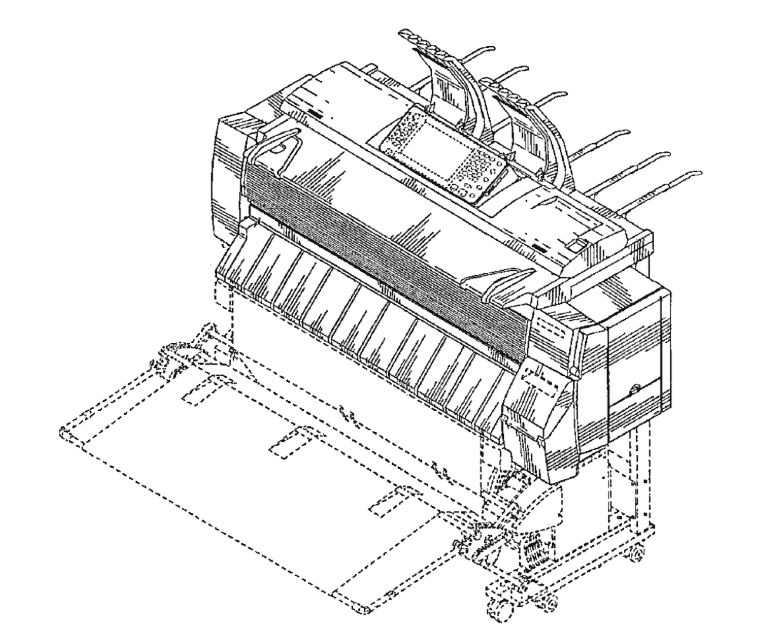

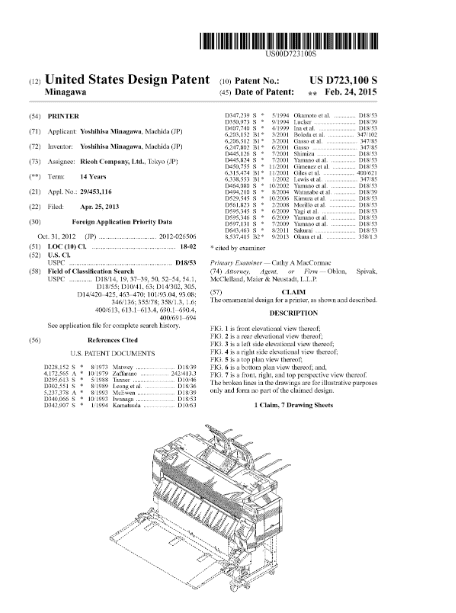

An example drawing is below for US Patent D723,100 for a “Printer”

The bottom portion of the printer – where the paper could be fed in – and the entire assembly/structure for holding the printer up is in dashed lines. This means it is not claimed, and therefore no matter what tray holder or structure to hold up the top portion in solid lines is used, it will infringe if the shape/ornamentation is substantially similar to the patented design.

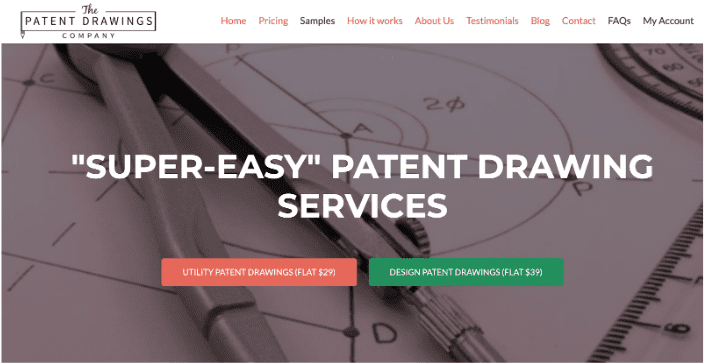

Now, the current market cost for patent design drawings varies quite a bit. I have found a few resources that may help you price them out:

- https://thepatentdrawingscompany.com/ has very low flat-rates for drawings quoted on their website:

- https://www.legaladvantage.net/ip-illustrations/design-drawings/ does not quote their prices on the website, but they do have some very good instructions on how to submit photos of your invention if you have it.

- Combined with Legal Services: This option is very popular for law firms to include “unlimited” or “free” drawings with the preparation and prosecution of the patent applications. The law firm takes the risk of any cost to rework or refine the drawings as it goes through final iterations leading up to the actual filing.

No Provisional Design Patents

For those of you familiar with utility patents, a very common way to get “patent pending” status is to file a provisional patent application. The (utility) provisional is a less formal way of protecting the broadest form of your invention and will lock in a priority date so that a follow-on non-provisional utility patent application may be filed within 12 months.

Unfortunately, Design Patent law under 35 USC 171 does NOT allow a provisional type of application. Therefore, an inventor needs to be completely finalized with the design when filing. It is not possible to modify/change the filing once submitted. This is likely the case because of how relatively simple design patent applications are compared to their utility patent counterpart.

I have below an image of a design patent we looked at above for the printer – the entire “specification” of the patent is ONE PAGE!!

You can see here as well that the “claim” is just a one-liner: “The ornamental design for a printer, as shown and described.” The truth is, that there is NO description…the beauty is in the figures/drawings. The Attorney that drafted that wording is very wise, as they let the drawing tell the story.

Statutory Bars & Deadlines!

Just like with utility patents, inventors need to be VERY careful not to invalidate their potential patent claim by disclosing or selling their invention prior to filing.

There is a 12-month grace period here in the US after any publication or sale is made from when the patent application must be filed, or else is it invalid for protection. ***Please see the 6-month grace period for international design patents below as well.

Publication:

This is really any published information available to someone of ordinary skill in the art/industry. In other words, if it’s findable, then it will start the timer. There is a small caveat here, in that if what was published was a very generic/high-level depiction of the invention (sort of like a teaser powerpoint) without actually disclosing the invention, then it will not toll the statute for those unpublished/undisclosed aspects.

Sale:

If you’ve sold your invention more than a year ago, you are not eligible to file for patent protection!!! I know… this is probably breaking a few hearts. If you’re not sure if you did, then set up a consultation and let’s confirm.

And, if you’re heart is not already broken, I have another rule that was decided just last year by the Supreme Court. Even if you offer to sell your invention more than a year prior to filing, it can be later invalidated!

The reason behind publication and sale bar is to disincentivize inventors from commercializing their inventions prior to sharing what they have come up with via the patent system. The overarching purpose of the patent system is to help us all become wiser and smarter by having inventors share what they’ve created with the US (and the world for that matter).

Of course, for sharing how to make and use their invention, the government gives them that 15 or 20-year monopoly and exclusive rights to make, use, and sell their invention.

International Filings (PCT and others)

A very important aspect of statutory bars and design patents specifically is that there is only a 6-month publication/disclosure window if it is used as the basis of an international design filing. This means that if you have published or disclosed your invention more than 6 months prior to filing, it will be invalidated in some Non-US jurisdictions.

Design Patent Prosecution

Prosecution costs are those costs incurred after submitting the design patent application. Usually, the application is assigned to a USPTO examiner, and you hear back within a few months whether the application is approved or rejected. If its rejected, it is called an “office action”.

Office actions can come in many flavors. The examiner will always provide the citation/reference number and provide some rationale as to why they rejected based on one or more reference.

Without getting into office actions too much here, the inventor (along with their attorney) must respond to the office action usually within 3-6 months. The response can be simple amendments and trivialities, or it could be very substantive and require research and the like.

The main variable on cost is how aggressively the attorney fights on behalf of the inventor. Usually, this is something that the attorney and client agree on before the answer/amendments/legal argument is submitted back to the examiner.

The more aggressively the office action response, the higher the likelihood of receiving a second or follow-on rejection (or even a Final Rejection). Thus, the cost will go up with a more aggressive response.

In Summary

Ultimately, like with any patent, the cost of a design patent can vary depending on different variables and nuances. That said, hopefully this guide gives you a better overall idea of what you are walking into!

To recap, today we discussed:

- Quick summary of design patent cost

- Why you should care about the cost

- Design patent searches

- Drawings

- Why there are no provisional design patents

- Statutory bars & deadlines

- Design patent prosecution

Now, you should be one step closer to planning your patent journey so that you too can Go Big and Go Bold℠ ! Based on the cost of a design patent, do you feel prepared to tackle your patent journey? What new thoughts and questions do you have? Start a conversation and let us know!

Legal Note: This blog article does not constitute as legal advice. Although the article was written by a licensed USPTO patent attorney there are many factors and complexities that come into patenting an idea. We recommend you consult a lawyer if you want legal advice for your particular situation. No attorney-client or confidential relationship exists by simply reading and applying the steps stated in this blog article.