Money, money, money!!! OK, it’s time to (finally) bring in those greenbacks, right!?

You’ve proven to the world that you know how to be bold. You’ve done the incredibly hard work to invent something new, useful, and non-obvious. Through research, diligence, tedious application drafting, and cunning responses to USPTO examiner office action rejections – you’ve overcome! You’ve got a GRANTED patent.

Now that you have that gorgeous ribbon copy of your patent with your name on it, everyone will know where to find you, what you’ve created, and will start to line up outside your door ready to buy one, right?

As you may have guessed… NO WAY! Sorry, if you thought by virtue of just having the patent in hand you’d begin to see commercial success, think again. Having a patent is the security of a novel invention – the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing your invention without your permission. There is no guarantee of money with a patent – you gotta make it happen in the marketplace.

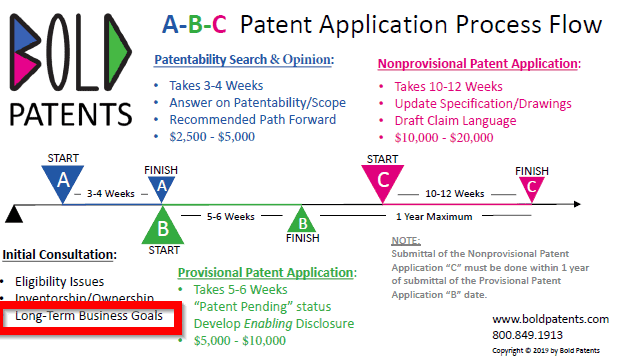

So, for just this reason, we plant the seed that the investors we work with will need to hustle very early on in the process. In fact, as you can see from the below chart we start asking about “business goals” and “business plans” from the get-go.

There are typically one of two routes inventors take: business ownership or licensing/selling. These are two very divergent paths, as one (business ownership) begins to take on more and more work (with the potential of more gain) and the other is a much clearer path to streamlined short-term monetary gain.

We ask which path our clients are leaning toward right up front so that we can be smarter about making referrals to key professionals (e.g. business attorney, CPA, bankers, software developers) that will be necessary as the business goes from idea to prototype to entity formation, shareholder’s agreements, outside investment, hiring employees, and growth/maturity.

These are the two paths to making money with patents:

- Business ownership around a core technology that is patent protected

- Making Money by enforcing patent rights and excluding others from competing in the same market (for a limited time)

- Sale or License of patented technology

- Making Money by selling (all or portion of rights) to a patented technology whereby a lump-sum or royalty payment is received by the seller/licensor

Today, I’m going to be focusing on the Sale of patented technology.

There has been many-a-lesson/blog on how to start/run a budding technology business, and so (at least for now) I’m not going to attempt that.

And, I’m not going to write about licensing patents (at least not here). This is a subject that I have actually just written an article about in my 10-Part Guide to Patent Licensing. Check that article out to get the full scoop on how to structure a licensing deal and what to expect when you monetize your patent rights by allowing another party to exercise one or more of the “make, use, sell, import” rights you get when you acquire a patent.

The bulk of what I’m going to discuss today surrounds how to think about negotiating and structuring a patent sales contract. But, it should be clear that there is a huge amount of work that goes into lining up a willing and able buyer of a patent.

Patent sales make sense when the seller does not want to participate in the technology development (at least not any longer) and truly wants to wash themselves clean of any involvement (including enforcement) of the underlying patent rights. A sale is a permanent clean break, and an opportunity for both sides to cleanly exchange ownership without much (if any) strings attached afterward.

The opposite is true of a license agreement. As you saw in the licensing article, there are big obligations on both sides to maintain the relationship and performance, and the term is typically only a few years at best. This is especially true of exclusive licensing contracts.

Ok, so let’s jump into it. I have laid out below the key areas of a patent sales contract that I am going to discuss in great detail below:

Section 1: Identification of the Parties

Section 2: Parties’ Intentions

Section 3: Patent Rights

Section 4: Prior Licenses

Section 5: Purchase Price

Section 6: Recordation at USPTO

Don’t forget that it’s going to take hustle to find a willing buyer of your patent rights. The approaches to getting there are vastly different. I mean, you may find that you start by accusing a business/individual of patent infringement, but end up being willing to sell your patent to them. It could be like finding a hidden business partner.

Or, it could be that “selling” your patent rights is just a matter of due course, as is the case often when companies start up. The founders of the company (often times the inventors) will “assign” (another word for selling) their rights in the patent to the company in exchange for money/rights/shares, etc.

Section 1: Identification of Parties

Once you find a willing buyer for your patent, it’s important to identify the right people or entities that are doing the buying and selling. It sounds simple, but can be problematic if there are any stones left unturned.

The primary way deals can go sideways is if the patent (or multiple patents, called portfolios) are assigned to a company and not all shareholders or owners of that company agree. The classic example is when a contract is written up between buyer and seller (the inventor) to purchase the patent asset, but in actuality, the inventor previously assigned their rights to the company.

So, doing your homework up front to identify who the OWNER(S) of the patent is/are becomes required diligence for any deal of this type.

Here is some standard language which is commonly used to start a patent sale contract:

This PATENT SALE AGREEMENT (”Agreement”), dated as of [DATE], is made by and between [NAME OF SELLER], a [STATE OF ORGANIZATION] [TYPE OF ENTITY] (”Seller”), and [NAME OF BUYER], a [STATE OF ORGANIZATION] [TYPE OF ENTITY] (”Buyer”).

Now, apart from the complication related to inventorship vs. ownership identified above, it is also important for the buyer (either as an individual or an entity) to research each patent that is being purchased in the agreement and confirm that the seller’s entity itself owns all patent assets.

With larger organizations, it is actually quite common to have subsidiary entities owned by the seller, and some of the patent assets being sold might actually be owned by one or more subsidiaries.

If subsidiaries are owners of even one patent asset that is being sold, they need to be named separately in list form following the parent entity to assure that all rights are being conveyed properly.

Now, some things should go without saying, but if there are individual patent owners here or entities, spelling is absolutely critical and it should be confirmed that the legal names are used. In addition, making sure the type of entity (LLC, C-Corp, S-Corp, etc.) is not assumed but is confirmed with the secretary of states for which each entity is formed.

Section 2: Parties’ Intentions

I really like putting this into the patent sale agreements, as it just clarifies what each party intends to do with the agreement. It has very little information or legal effect other than a very readable, logical statement that everyone can understand.

Here is an example of such a clause:

WHEREAS, Seller wishes to sell to Buyer, and Buyer wishes to purchase from Seller, all [of Seller’s] right, title, and interest in and to certain Patents (as defined below), subject to the terms and conditions set forth herein.

I know… “seller wishes to sell”, and “buyer wishes to purchase”, haha… overly simple? I think not, it really clarifies what each party wants to do and further defines the goals of the agreement!

Now, something that can get more specific is if we wanted to itemize the patent number here. If it is just one patent being sold, I recommend adding it in here. If there are more than one, then it should be in a separate schedule where this clause identifies the schedule (A, B, C, etc).

Big note is that this part of the sales agreement is where you can add language about a lease-back to the inventor/seller. A lease-back is a license that allows the seller to continue to make and/or use the patented invention. This is usually the case if the seller wishes to continue innovating and wants to be free from infringement suits for doing so.

A final note is that if this agreement is part of a settlement from a dispute (which is how many of these sales are struck), that should be pointed out. An example clause could be: “parties stipulate that upon execution of this agreement, that the proceedings be dismissed with prejudice…”

Section 3: Patent Rights

Now, patent rights (in the geographical area they are bestowed) are actually best understood in terms of what they restrict others from doing. In that sense, they are written in the negative. The major “rights” consist of the big 4, as follows:

- Prevent others from making the invention

- Prevent others from using the invention

- Prevent others from selling (or offer for sale)

- Prevent others from importing the invention

When you are selling a patent, it is implied that the seller is selling ALL of the patent rights. So, that is the default interpretation unless otherwise specified in the sale agreement. Here is a typical sale agreement:

NOW THEREFORE, in consideration of the mutual covenants and agreements set forth herein and for other good and valuable consideration, the receipt and sufficiency of which are hereby acknowledged, the parties hereto agree as follows:

Subject to the terms and conditions set forth herein, Seller hereby irrevocably sells, assigns, transfers, and conveys to Buyer, and Buyer hereby accepts, all [of Seller’s] right, title, and interest in and to the following (collectively, “Acquired Rights”):

The patents [and patent applications] listed in Schedule 1[, all patents that issue from such patent applications,] and all [continuations,] [continuations-in-part,] [divisionals,] [extensions,] [substitutions,] [reissues,] [re-examinations] [and renewals], of any of the foregoing (”Patents”)[, and any other patents [or patent applications] [from which any Patents claim priority] [or] [that claim priority from any Patents][, and all invention[s] disclosed [and claimed] in any of the foregoing] (collectively “Acquired Patents”);

I like this way of spelling it out in the contract. There is a key point that in order for a contract to be binding and enforceable on all parties, there must be MUTUAL CONSIDERATION. This just means that each side must be giving up something. In this case, we specify that there is “good and valuable consideration”. Now, usually this must be buttressed by a real dollar amount, but it’s good to lay it out.

The “irrevocably” term here is key. A sale is final, as opposed to a license which may be renewed or subject to performance clauses and changes in ownership as the patent term runs its course. The key to a “sale” is this irrevocability and finality of the transaction.

Instead of trying to list all the patents, applications, and any technical know-how (trade secrets) which are sometimes lumped into IP sales agreements and patent sales agreements, the BEST way is just refer to a Schedule A or a placeholder term like “Acquired Rights” which are surely defined in the contract separately.

Note on the green highlight: the BUYER will want to avoid any possibility that the seller’s rights in the patents are in any way incomplete, limited, or qualified.

Therefore the clarification that the transfer of rights is “all right, title, and interest” in and to the acquired patents as opposed to “seller’s” rights (which could be a more limited scope of rights) as the seller could own a partial interest in patents with other individuals or entities.

Last note, on the pink highlight sections – the buyer and seller can negotiate a lot on these pending rights of patent applications. The value is arguable, but the idea that the scope of rights can be enlarged is usually in the buyer’s favor to include.

Section 4: Prior/Existing Licenses

As it happens, over the course of a patent’s life, it may be licensed. In fact, this is how many infringement suits end up getting settled. One party infringes the patent of the other, and the infringer is allowed to continue making/using/selling the product but not without paying a royalty to the patent owner.

At the time of proposed sale, there could be license agreements already in place associated with the patent assets. That means there are strings attached, and the buyer isn’t buying the patent portfolio “free and clear” as it were, so additional language needs to be added to control much of it. Here is an example:

The Sale further comprises the following:

- All licenses and similar contractual rights or permissions, whether exclusive or nonexclusive, related to any of the Acquired Patents, including those licenses listed on Schedule X (”Licenses”);

2. All royalties, fees, income, payments, and other proceeds now or hereafter due or payable to Seller with respect to any of the foregoing;

3. All claims and causes of action with respect to any of the foregoing, [whether accruing before, on, or after the date hereof/accruing on or after the date hereof], including all rights to and claims for damages, restitution, and injunctive and other legal and equitable relief for [past, ]present[,] and future infringement, misappropriation, violation, breach or default; and

4. All other rights, privileges, and protections of any kind whatsoever of Seller accruing under any of the foregoing provided by any applicable law, treaty, or other international convention throughout the world.

This is a nice way of summarizing all potential issues that could arise out of the sale of an asset that is currently bringing in money or under an obligation via a separate earlier signed license agreement.

What’s also cool is that this language in (3) allows and considers any past, present, and future litigation. The past/present litigation is negotiated pretty often.

Section 5: Purchase Price

This is probably the TOP concern and the place that buyers and sellers focus on. This is the most highly negotiated part of the sale of the patent assets.

Here is some example language of what the purchase price portion of a patent sale should look like:

1. Purchase Price.

(a) The aggregate purchase price for the Acquired Rights shall be [PURCHASE PRICE IN WORDS] US Dollars (US$[PURCHASE PRICE IN NUMBERS]) (the “Purchase Price”).

(b) Buyer shall pay the Purchase Price within [NUMBER] [business] days following the parties’ full execution of this Agreement. Payment shall be made in US dollars by [wire transfer of immediately available funds to the following account: [ACCOUNT INFORMATION FOR WIRE TRANSFER]/[PROCEDURE FOR PAYMENT]].

(c) If Buyer fails to make timely and proper payment of the Purchase Price, Seller may[, in addition to, and not in lieu of, all other remedies,] terminate this Agreement effective immediately on written notice to Buyer.

2. Deliverables. Upon execution of this Agreement, Seller shall deliver to Buyer the following:

(a) an assignment in the form of Exhibit A (the “Assignment”) and duly executed by Seller, transferring all [of Seller’s] right, title, and interest in and to the Acquired Rights to Buyer; [and]

(b) the complete prosecution files, including original granted patents, for all Acquired Patents in such form and medium as [reasonably] requested by Buyer [together with a list of local prosecution counsel contacts], and all such other documents, correspondence, and information as are [necessary/reasonably requested by Buyer] to register, prosecute to issuance, own, enforce, or otherwise use the Acquired Rights, including any maintenance fees due and deadlines for actions to be taken concerning prosecution and maintenance of all Acquired Patents in the [ninety (90)/one hundred eighty (180)/[NUMBER]] day period following the date hereof[; and/.]

(c) Copies of all consents, permissions, and agreements required for the transfer of Licenses.

So, typing in $123,400 is simple enough, but the other key terms here to think about in regard to actually getting the money is the process by which money will be transferred (check, cash, money order, wire, etc.). Also important is the TIMING, as in when the payment must be made.

In the highlighted area, you can see that if the money is not received, then there is a breach of contract and the sale agreement is terminated.

KEY: If the sale agreement gets terminated by operation of the breach clauses, that would immediately risk putting parties in an infringing state! This would mean an inevitable future conversation and/or lawsuit.

Section 6: Recordation at USPTO

As with any transfer of ownership/title, recording the agreement at the USPTO is vital to establishing publication (and therefore constructive public knowledge) of the transaction and the current owners.

Therefore, it should be determined who is responsible to record the transaction and tie up any loose ends leading up to that.

Here is some example language:

Without limiting the foregoing, Seller shall execute and deliver to Buyer at Buyer’s expense, such assignments and other documents, certificates, and instruments of conveyance in a form [[reasonably] satisfactory to Buyer and] suitable for filing with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (”USPTO”) [and the registries and other recording governmental authorities in all applicable jurisdictions (including with respect to legalization, notarization, apostille, certification, and other authentication)] as [reasonably] necessary to record and perfect the Assignment, and to vest in Buyer all right, title, and interest in and to the Acquired Rights in accordance with applicable law.

As between Seller and Buyer, Buyer shall be responsible, at Buyer’s expense, for filing the Assignment, and other documents, certificates, and instruments of conveyance with the applicable governmental authorities; provided that[, upon Buyer’s reasonable request,] [and] [at Buyer’s expense,] Seller shall take such steps and actions, and provide such cooperation and assistance, to Buyer and its successors, assigns, and legal representatives, including the execution and delivery of any affidavits, declarations, oaths, exhibits, assignments, powers of attorney, or other documents, as may be [reasonably] necessary to effect, evidence, or perfect the assignment of the Acquired Rights to Buyer, or any of Buyer’s successors or assigns.

There are specific processes that must be followed in order to record a patent assignment (sale) under MPEP 302 here.

The recordings are kept at the USPTO’s Patent Recording Office, and you may record documents using their “Electronic Patent Assignment System (EPAS) here.

Also, You can find recorded documents using their website here

In Summary

Part of the patent journey for many entrepreneurs is making a profit by selling that patent and moving on to their next great idea.

The six important things to keep in mind if you plan to do this are:

- Identifying the parties involved

- Establishing the parties’ intentions

- Knowing patent rights

- Recognizing prior/existing licenses

- Establishing the purchase price

- Recordation at USPTO

Now you’re ready to start the selling part of your journey! Do you think you’ll be one of the inventors who sells their patents, or are you going to establish your own business around your invention and sell the idea itself?

Legal Note: This blog article does not constitute as legal advice. Although the article was written by a licensed USPTO patent attorney there are many factors and complexities that come into patenting an idea. We recommend you consult a lawyer if you want legal advice for your particular situation. No attorney-client or confidential relationship exists by simply reading and applying the steps stated in this blog article.