So…you’ve got an invention! Or is it just an idea? Take a few minutes and figure out here.

Maybe you’ve already done the hard work of getting a professional patent search done and have filed a provisional patent application already? Kudos to you for being patent pending!

…Or, maybe you’ve even filed a nonprovisional patent application? (Nice work! psst, I hope you are using a Patent Attorney – read why here)

And just maybe, some of you have your patent GRANTED! If so… CONGRATULATIONS on that achievement. You’ve accomplished something truly great…

Now, let’s get real – I’m guessing the vast majority of you reading this are hard working planners, and you’re interested in learning more about licensing in a proactive manner before even starting.

Right? Well, no matter where you are in the patent process (see below) – this article will be good for you.

Not sure you want to go down the entrepreneur’s path of starting up a new company, raising money, hiring employees/contractors, managing a team and hustling to please investors/shareholders?

It’s a big decision whether to start/grow a business of your own, or instead to seek to license/sell the technology.

What’s nice is that you don’t have to know it all up front. It’s a journey, and you can (and upon gathering more information/research) and often times SHOULD change your mind.

Alright, so let’s get to it!

There are 10 key considerations to take when putting a solid patent license together, and they don’t necessarily have to be taken in order. They are as follows:

Part 1: Determine the Underlying Patent Rights

Most patent license agreements involve at least one granted patent (and usually include a portfolio of several issued patents).

However, it is very possible to license the prospective rights of a pending patent application, whether it be on its own or as part of a portfolio along with other pending patent applications and granted patents.

Know that negotiating a pending patent application will be more difficult than a granted patent, depending on a number of factors such as prosecution history (i.e. what, if anything, the examiner has said on the record regarding patentability).

A granted patent at least has the USPTO’s stamp of approval on it, and your rights are more likely valid than a pending application.

Whether you’re dealing with a pending patent application or an issued patent, it ALL COMES DOWN TO THE CLAIMS.

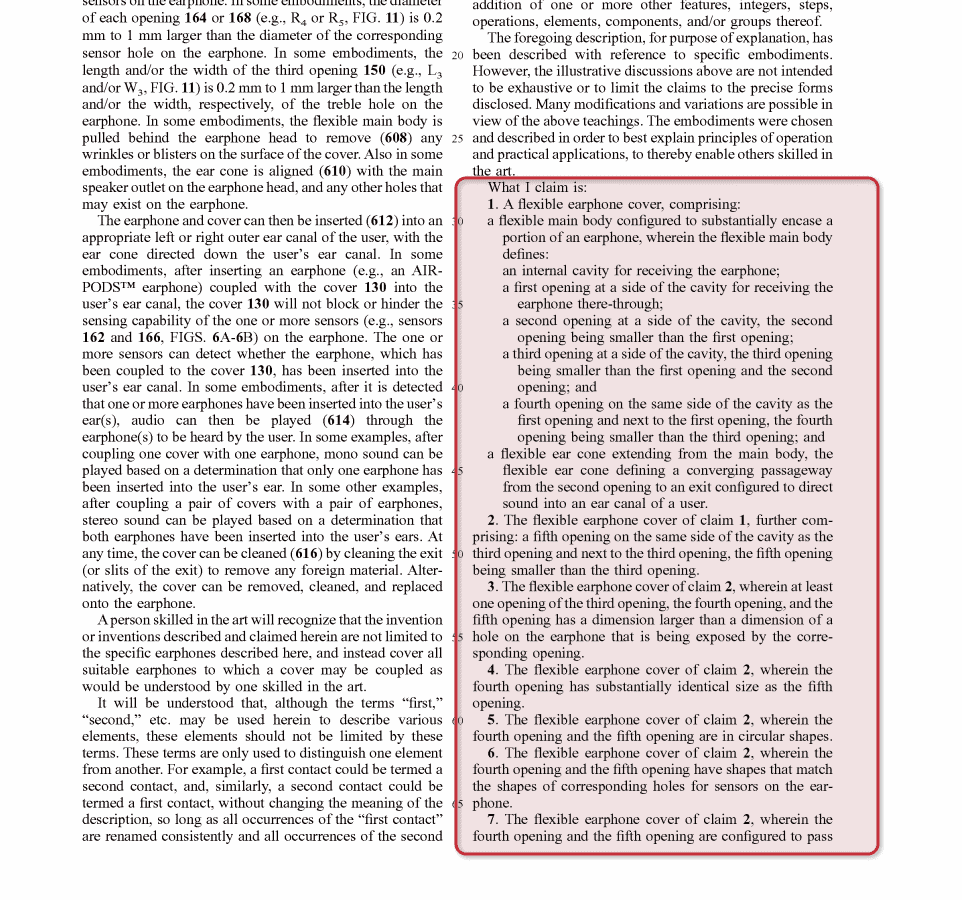

For Utility patents, the claims are purely written form as shown below with an earphone cover Patent US 9,736,564:

While there could be tomes written about how to understand patent claim language, we won’t dive into that now…

The claims, as discussed in the above article and in our example here provide the scope of RIGHTS that will be granted in a patent license. There are some key things to consider when entering into a negotiation about what the scope of rights are:

- Whether there is just one patent, or if there is a family/portfolio that needs to be analyzed (you don’t want to end up licensing just one small aspect of a technology patent without knowing all other patented/pending rights)

- Current infringers or any known infringers (risks that others have already unlawfully entered the market – more on this later)

- Prosecution history is important – the back and forth that the patent application went through with the examiner. This is important to understand if the Patent Attorney gave up any rights either through disclosure or by getting around prior art

- A plain reading of the claim language to appreciate to what degree competitors will or will not be able to design around your invention.

It comes back to the fact that the real VALUE of a patent is the right to EXCLUDE others from making, using, selling and importing the patented product/system into the geographic area of exclusivity.

So…how much is it worth to you to be able to keep everyone OUT?

To point out the obvious (which is sometimes helpful) – if you are the licensee (the person/entity receiving the rights the invention), just having a license to make/use/sell does not make you money. You’ve got to go out and make it happen.

By the same token, if you’re the licensor (the one giving up the rights to the invention), by closing a license deal, your work is not done. You’ve often times got to encourage/help the licensee make money so that you can get paid.

Part 2: Due Diligence – Find out What You Don’t Know

This section is obvious, but I gotta mention that you’ve GOT TO DO YOUR HOMEWORK before negotiating and entering into a patent licensing transaction.

Even if this was obvious, what might not be so obvious is what KIND of research?

Validity analysis. Even though the USPTO allowed a claim set to be patented, doesn’t mean it’s bulletproof. Any who’s shooting bullets? The courts.

Before taking for granted the patent claims as supreme and unshakable, you’ve got to understand that patent claims are issued by the Administrative body, called the USPTO, and the ability to enforce those rights MUST come before the courts either in the PTAB or Federal Court.

Further, as many cases get decided by the Supreme Court each year, and even more cases at the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, patent law itself constantly changes.

Therefore, the scope, enforceability and VALUE of a patent claimset changes all the time.

Therefore, it becomes critical to really know what you’re buying/licensing before you make the transaction.

Let’s do an analogy to the real estate industry… Why do you think every bank, before it lends money, requires that a home inspection and appraisal be done on the home? Because a house is a complicated thing and should be evaluated by a professional.

Same is true for a Patent. It’s a complicated beast, and a professional should review, survey, evaluate and provide notice of any red flags or issues and give insight as to what the valuation of the scope of rights is.

Part 3: Negotiation Strategy – Plan to Make a Solid Deal

Don’t go into a negotiation cold. These are very big transactions, and oftentimes emotions can creep into the room, and distract you from making a sound business decision.

Over the years, I’ve learned there are really only TWO major ways in which you MUST plan in advance of the negotiation in order to have success:

- Write down Goals for deal: If you could imagine a PERFECT deal, what would it look like? Remember, this is not “what is feasible” or “likely” but rather IDEAL. At least write this down so you know how close to that you are getting as you work through negotiations.

- Write down “Walk-Away” terms: These must be true deal-breaker terms. Try to keep these as low as possible, but make them REAL, ACTUAL numbers. Of course, the hardest thing will be to actually stick with them if you’ve crossed the line in negotiations and need to walk away.

That’s it… 🙂 My “Secrets” to negotiating big deals!

Now that you’re ready to get to the negotiation table, let’s get to the core of what you’ll actually be negotiating: The Grant, The Term, Territory and Royalty!

Part 4: The Grant – What is Being Licensed?

I’m really hitting this point home in this article. But you gotta keep your eye on the ball, the ball being the PATENT CLAIMS. Yes, this is what’s being granted (either through sale or license) and it cannot be overlooked.

Now, while it’s possible to only license some of the claims of an invention, I’ve never seen this happen. So it will be worthwhile to evaluate the entire claim set of the underlying patent (and patent portfolio if there’s more than one) to fully appreciate the scope.

Based on how you define terms in the license agreement, certain words become SUPER important. Such as “WHAT IS GRANTED IS…” which becomes the hallmark of the license agreement.

One of the major elements of the “grant” is how to list the patent numbers. It can be done in many different formats, but as long as the actual patent number and the numbered claimset is identified, it should work.

Part 5: Who will it be Licensed To? “Exclusivity and Sublicenses”

Another element to consider is exclusivity. The license is either exclusive or nonexclusive.

Running Example: I’m going to slowly build up an example grant clause which incorporates the learnings from here:

“What is granted is an exclusive license all 20 claims on US Patent Number 20,000,000…

An exclusive license means that the licensee (the one receiving the license) will be the ONLY one able to exercise the rights granted under the license in the geographic area described. Generally, these are going to be more expensive to secure a license for.

If nonexclusive, then it therefore means that other licensees could be given the same/similar rights simultaneously, or under certain restrictions as defined by the agreement.

The ability for the licensee to sub-license is an important point of negotiation when defining what is being granted and should be considered when making the grant.

“What is granted is an exclusive license without the ability to sublicense all 20 claims on US Patent Number 20,000,000…”

There are other conditions to the grant, which should be elaborated elsewhere in the contract but that don’t need to be in the grant clause itself:

- Whether the licensee/licensor has the ability to use the invention to improve on the rights granted (design around)

- Whether they are going to allow the inventor a license back

- Limitations of government intervention (anti-competition rules)

- Limiting certain uses of the patent (for ethical or other religious reasons)

- Govern which jurisdiction will interpret the contract (State, Country, etc.)

Part 6: The Term – How Long will it be Licensed?

The first thing to think about is actually NOT how long will the license be granted for, but how long the patent will be enforceable for! How horrible would that be if you contracted to pay an inventor for a license AFTER the patent became expired and it was part of the public domain! Ouch…

So, yes – make sure you know for how much longer the patent rights will be enforceable for, down to the date. Also, in order for patents to have a life for their full 20 years from the filing date, that maintenance fees must be paid to the USPTO (and they can be quite costly). If fees are not paid on time, the patent will go abandoned EARLY.

Typically, patent licenses are granted in terms of years, not months or days. Depending on markets or industries, certain shorter time periods can be negotiated (such as 5 years) even if the patent duration is over 20 years.

This is so that the parties will have an opportunity to renegotiate should market conditions change. This is a risk for both parties to build in a renegotiation though.

“What is granted is an exclusive license without the ability to sublicense all 20 claims on US Patent Number 20,000,000 for a duration of 5 years…”

Part 7: The Geographic Scope – Where will it be Made/Used/Sold/Imported?

When negotiating single patents, this section is much easier. The geographic scope is, by definition, the legal scope of the one patent. For example, if the underlying is one patent, the geographic scope is limited to the entire United States.

However, when it comes to a patent portfolio that spans multiple countries (and therefore different markets), the geographic scope becomes more important. Some patents will only be licensed for use in the country where rights are given, whereas others will be licensed as “worldwide” or “anywhere in the universe”, etc.

The default patent licensing language is “worldwide” when giving a license to someone which gives the most amount of rights that is possible under the patent itself. And, as mentioned above, this geographic indication outside of the country of patenting actually carries no weight – it still sounds good, and also would disallow the licensor from pursuing any further protection in other countries during the license agreement.

“What is granted is an exclusive, worldwide license without the ability to sublicense all 20 claims on US Patent Number 20,000,000 for a duration of 5 years…”

Part 8: The Money – For How Much?

While there is (as you can tell from this article hopefully) a LOT that goes into a patent license agreement, the money is undoubtedly the HEART of the deal.

There are different types of payment structures, but the most common is a royalty based on sales. This is also called “earned royalties” – this will be a great way to drive the licensor to only get what sells.

However, it can come with some tricky scenarios where performance is king. Making sure the licensor (especially exclusive licensors) is actually doing what’s commercially reasonable to sell the product will be tough to enforce.

Another structure is what’s called periodic or “milestone” payments. This could be achieved by hitting certain sales goals/targets, user adoption, profitability margin, etc.

The nice thing about milestone deals is that neither party is going to get caught in the day-to-day grind (as can be the case for the earned royalties approach), and one can see the forest from the trees.

It definitely goes both ways though, if you stay too “high level” then details can get by you, and you’re way off course. However, if you’re only at the “detailed level”, then you may not realize you are not going to hit your big goal.

“Royalty rates” is another huge negotiation point. The amount or percentage of money that a licensor receives from the licensee will depend on many factors, but typically varies from between 3-10% of the sales price.

The majority of patent royalty agreements are struck between 5-7%. This means that if a patented product is sold for $100, the inventor/patent holder/licensor will make $5-7.

Easy math, right? Haha.

Now, you’re also going to want to contract for WHEN the money will be paid, not just how much. Typically annual, quarterly or even monthly payments can be made. Generally, the more frequent the payments, the higher the administrative challenge to bookkeep and maintain the records.

“What is granted is an exclusive, worldwide license without the ability to sublicense, all 20 claims on US Patent Number 20,000,000 for a duration of 5 years in exchange for 6% by revenue royalty payable quarterly…”

Part 9: Infringement: Who Enforces Patent Rights?

So, you license the invention to someone, and find out that there’s a 3rd party (that doesn’t have a license) that is ripping BOTH of you off now! You’ve got an infringer…now what?

As you likely remember from Patents 101 – there is NO PATENT POLICE!!! Patent owners (and their licensees) are 100% responsible for monitoring and enforcing their rights.

As all legal answers go, it depends. The biggest deciding factor is whether you licensed the invention in an exclusive or nonexclusive manner.

If non-exclusively licensed, then typically the licensor (the one licensing) will need to pursue the infringer to enforce the rights and the licensee is off the hook. However, the downstream licensee (and any of their sublicensees) will be VERY interested and vested in your enforcement.

If exclusively licensed, the licensee can be held to be responsible to at least join you (as the licensor) in enforcing the patent rights. Cool huh?

The reason here is that the licensor is depending entirely upon the licensee to help them see the financial benefit of the investment they made on the patent acquisition.

From a political/philosophical standpoint as well, the inventor should be rewarded for the innovation and the system exists to reward inventors for helping us all become smarter by sharing their invention with the world.

Long story short – when you license a patent, the effects of an infringer are multiplied, and ALL parties along a license chain are affected. The net result though is that an infringer of a patent that has been licensed is more likely to face a stronger opponent as now you’ve got several entities all financially motivated to take down an infringer.

Part 10: Termination – When is the License Over?

Along with how long the license will be for, it is just as important to contract for when the contract will end!

The “end” is also called “termination” – and there should be specific language around each of the following scenarios:

- If either party goes out of business (files bankruptcy), or is acquired by or merges with another company

- If the licensee doesn’t pay royalties: what is process, who gets what?

- Breach of the contract, specifically the performance clause (meaning licensee doesn’t move the product, seem unmotivated, etc.)

In Summary

Patents can be very complicated legal constructs, and the idea of contracting to grant one or more parties to perform some or all of those rights adds even more complexity to the mix.

When licensing, just make sure to remember the 10 parts discussed:

- Determine the underlying patent rights

- Due diligence

- Negotiation strategy

- The grant

- Exclusivity and sublicenses

- The term

- The geographic scope

- The money

- Infringement

- Termination

I’m impressed at your thoughtfulness to get this far, and to further your knowledge of patent law. Know that if you ever have any questions about the process or how to get started, you can visit our website at www.boldip.com, and schedule some time with an advisor.

How will you incorporate patent licensing into your venture?